45. EVA VERMANDEL - A SPACE BETWEEN CALLING AND CAPTURE.

The artist discusses her creative process.

‘I do wonder sometimes whether I’m just a vessel that captures things that get sent to me and need to be caught.’ E.V.

Eva Vermandel, Boy with Pink Aerosol, Stroud Green, 2006. Image courtesy of the artist.

The first time I saw your works, I was immediately amazed at how you communicate emotion - images that are so luminous they can be seen when the eyes are closed - at what point did you know that photography was your way forward?

Thank you so much, emotion is what I try to communicate so it’s incredibly gratifying to hear that that is what you take away from my work, and so intensely.

I was about four-five years old when I first picked up a camera. My father was an amateur photographer and we’d often go for walks together with his camera in tow. He’d occasionally let me take a picture with it. Back then, in the late 70ies/early 80ies, photography was precious and expensive, so this was done sparingly, we were not a rich family. By the time I was a teenager, my dad let me use his Contax to shoot the odd film, and the curious thing is that the pictures I took back then have the same intensity and atmosphere they still have now. So I think it came embedded in me.

Eva Vermandel, Bart, 1988. Image courtesy of the artist.

That said, I’ve often battled with the actual medium of photography, with its directness. The art I get drawn to most is painting. There’s such a freedom to bring the emotion of an experience to the fore in painting, rather than the de facto ‘this is what occurred’ element that often gets represented in photography. The result is that my practice revolves around breaking through the directness that is inherent to photography.

For years I found this directness a restraint, and up until a couple of years ago I did toy with the idea of switching to painting, until I realised that my battle with the directness of the medium is what makes my work so singular. I revel in pushing the camera to its limits, and this often happens not through special effects but simply through intense observation. This can go so deep that I feel that it is me who is being swallowed up through the lens, rather than the other way around.

Over the years I have become aware that I don’t ‘create’ my work, but that I ‘catch’ it. The sharpening of my craft lies in training my instincts to feel these moments brew and trust that whatever it is that needs to be captured will get thrown in my direction. Even on the few occasions that I have worked in a constructed manner, there will still be elements within that constructed setup that guide me rather than me guiding them.

'Boy with Pink Aerosol' seems to be such a pivotal image, how did that portrait come into being?

I personally wouldn’t call it a portrait, rather a state of being. At the core of the image lie the gestures of the arms, which are both engaged with elements you can’t see, and the tilt of the head and neck. There are also details that are so slight that the viewer needs to fill them in. It’s a puzzling work and it requires active looking. I love what Francis Bacon said about art: “the job of the artist is to deepen the mystery”. I fully empathise with that.

It happened upon me in the summer of 2006, when I had gone for a walk with my Mamiya 7 near where I used to live. I came across a group of teenagers spraying graffiti on a section of Parkland Walk, north London. This is a disused railway track that is now a nature reserve and favourite haunt for locals. Several of the leftover structures of the railway get graffiti-ed on a regular basis and that afternoon these boys were having a go at it.

I asked if I could photograph them. I remember that the boy in the photograph is called Phil. He had an elegance about him that drew me to him more than the other two boys. I think he must’ve been around 16 at the time, so he’ll be well in his thirties now. I deliberately underexposed the negative to get the background to drop away and to enable his skin, which was luminous, to become even more radiant.

The post-production of this work was as important as the creation of the work itself. To achieve the depth of the luminosity of the skin, the underexposure of the negative was pretty extreme, about three stops; afterwards I had to rebuild the parts that had nearly disappeared. All in all it took me about five years to get it to a point where it felt right. It’s not the only work that took me years to finish.

I love the fact that it can take me years to get a photograph ready for print. It reinforces the long-time-frame undercurrent of the work. A lot of artists I admire have elements of this in their workflow too: Edvard Munch often reworked his paintings or revisited the same theme/setup he’d painted before. He once said “I don’t paint what I see; I paint what I saw” which resonates with me immensely. He’d spend hours just sitting opposite a person, not touching his canvas to then paint them after they’d gone. The galloping horse he painted in 1910 was done from memory. He must have deeply absorbed what he saw in those split seconds that it was happening to be able to paint it in such a dynamic way afterwards.

Edvard Munch, Galloping Horse, 1910-1912, Oil on canvas, 148 x 120 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Pierre Bonnard is another example of prolonged-time artists: he’d show up at the opening of his own exhibitions, brush and paints in hand, to add more touches to the works installed on the wall. Or he’d repaint a whole section of a painting years after its initial completion. He’d ask sitters to walk around as he was painting them, which enabled him to shift the focus on the rhythm and colour of the work rather than the ‘likeness’ of it. One of his sitters, Dina Vierny, said that he asked her to walk all the time; to ‘live’ in front of him, trying to forget he was there.

You need time to process what is happening AND life is in constant flux. These two factors combined mean - for me at least - that art needs space to breathe and will never be, neither should be, ‘finished’.

The title of your book, 'Splinter', is fascinating, the idea that elements of a whole can fracture and get underneath your skin - I really feel that within your works. What are the key images that you return to within your collection and what do they tell you?

Thank you, yes, the name Splinter was suitable for the work. It has many ways of interpreting it, which I like. Aside from the splinter as something that gets underneath your skin there’s also the fact that a splinter comes from a tree, a beautiful thing (trees are such a joy!). Then there’s also the feeling of being splintered. And there’s the famous Adorno quote: “The splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass available”. It’s such a versatile word that can be used in so many different contexts and interpretations.

In terms of what the key images in my work could be: these often change. Over time works that were key get overtaken by other works and then things change all over again. The work is never static, it keeps evolving, within the existing work and in the process of the creation of the work.

This is also why Giorgio Del Buono of Systems Studio, who designed my website - and did so most beautifully and insightfully - created the randomisation of the Selected sections on the site. I love the way that every time the page gets reloaded different images will be thrown together: through this process new elements you - or I for that matter - hadn’t spotted before come out through these randomised juxtapositions.

As to ‘Splinter’ as a book, I now see it more as a collection of early works rather than a ‘project’ or ‘body of work’. I’ve completely stepped away from the ‘project’ approach that is so prevalent in photography. When I put work on display I like to mix up pieces created throughout my whole practice, old and new. New work can add a whole different dimension to older work and vice-versa; there’s always a dialogue: within the work, between the work. I find the idea of a ‘project’ far too constrained and it doesn’t fit with my thinking.

To get back to the point of key works: even though they often change, there are some works that were turning points in my approach to the creative process. One such work is Tree, Stroud Green, 2014, Which came into being because it had to: I could feel it calling me as I was walking down the street I used to live on. I got my point-and-shoot Contax T3 camera ready (which I started using for my artistic practice around that time and always carry with me) and when I turned the corner it was there. I even remember thinking “ha! It was you that was calling out to me!”. I took a couple of shots and walked on. The piece that came out is one I’m very fond of.

Eva Vermandel, Tree, Stroud Green, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

At that time I needed to break away from the aesthetically pleasing painterly style I’d mainly been working in up till that point. I needed something harder, something that would be both appealing and repelling. I do not like complacency in art, not as a viewer nor as a creator of art. This need to push boundaries does not come from the perspective of “aaah today I’m going to do something different, something subversive”; it comes because at some point the work calls out that this needs to happen. This image came into being because it had to. It ‘presenced’ itself and I caught it.

I recently made a film in collaboration with the composer Galya Bisengalieva, shot on my iPhone, an old SE. Once again, it was a case of something brewing, an invisible thread that I needed to follow. This came about through Galya’s invitation to create a film for a track on her album Polygon, which, after a couple of weeks of letting the music sink in, led to a first spontaneous piece shot from a double decker bus for the track Degelen. This set things up for further technical explorations on the device I was using and - finally - another ride on the same bus, the 197 between Sydenham and Peckham. It all built towards the film I landed on in the end, shot during that second bus ride, which is uncanny in its timing, composition, eeriness and perfect syncing to the music. It baffled both Galya and me afterwards, how deep the synchronicity is between the film and the music, and I can still barely believe it all came together the way it did.

Galya Bisengalieva - Degelen (Official Music Video)

I do wonder sometimes whether I’m just a vessel that captures things that get sent to me and need to be caught. It’s a funny thing to build a whole practice on chance; on sharpening the intuition to grab things rather than actively setting out to create work from scratch. It requires a leap of faith which I relish.

Your images evoke so many senses and yet you are known for creating photography, have you expressed your instinct through other media?

Oh yes, see above. I sometimes paint, mostly in watercolours. I recently did an audio-piece for an exhibition I had in Amsterdam in April 2023, and am working on another one for a future exhibition, and I’ve done three films up till now. As with everything, these things came about because they presented themselves to me in some way or other.

The three films I’ve done were shot using completely different tools: 35mm film, a Nikon D800 and my iPhone SE.

The first one, The Sea Is Always Fluid, with Aidan Gillen, was shot on 35mm. It had cinematographer Rachel Clark on camera and was one of Rachel's first films as a cinematographer back in 2011 (she now shoots feature films, among which I Am Ruth with Kate Winslet and her daughter Mia Threapleton last year). It came about because Panavision had offered Rachel a whole 35mm kit rent-free and she was looking for an opportunity to use it. I’d known Aidan for a long time (we used to see each other) and felt I’d never been able to capture him as I’d wanted to in a still. I especially wanted to capture his connection with the sea. I’d just had a good year financially so could afford the costs involved in a production like this (despite the camera kit being free, there was the insurance, transport, accommodation, processing etc to pay for still).

I had plans for what I was going to film, because when working in a setting like this, with all the cost involved and a whole team (Aidan, Rachel and the two camera assistants Tim Allen and Alejandra Fernandez) giving their time for free, you can’t go “ooh I think I’ll just see what happens and improvise on the spot!”. It was - of course - the spontaneous, everything-falling-into-place footage that we shot right at the end of the day that became the piece. The sun was setting, the sea had pulled back and formed a mirror on the shore. Aidan lay down onto that mirror, and as we were using the very the final piece of film, the flash of light you get when the celluloid is cut off, became part of the piece.

The second film I made is Blood Orange, shot on a Sunday afternoon in January 2018, in the living room of my former house. It came about through a prism of restlessness combined with boredom and an underlying emotional current, an avalanche that was heading my way which I wasn’t aware of yet at that point. It sat on my hard drive until earlier this year, post-avalanche, when the aforementioned exhibition I had in Amsterdam, with its theme of Transition/Transformation, created the perfect platform for its first outing.

The most recent film I made is Degelen in collaboration with Galya Bisengalieva, shot on my phone, which I spoke about earlier.

The audio piece I did for Amsterdam consists of readings of very brief excerpts of short stories by DH Lawrence, whose writing has had a major impact on me. This work was partly created to make visitors to the exhibition aware of the view onto the bay from the windows where this piece was installed. You can see bits of that view and hear these audio pieces on my Instagram account.

So to cap it all off, the space in which I exhibit becomes a work in itself too, with the same principles of fluke that apply to all my other works.

I realised while putting the new issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) together that I was also searching for myself within the works collected, which was an extraordinary realisation, can you share any thoughts about searching for answers within your practice?

That gives me enormous pleasure to hear. The last thing I want to do is force my thoughts and feelings onto the viewer, instead I love it when the work functions as a mirror that people can project their own thoughts and feelings onto.

I search all the time, but it isn’t answers that I’m looking for. I want to figure out what it is that I am searching for, which aspects of life I’m trying to explore and why. I don’t think there are any answers in life or art. Life is about openness and exploration - the more you open up to the world and the people around you, the more it enriches you.

With the current wave of self-obsession that came in the wake of social media and a higher level of affluence, people seem to have lost the ability to look outside of their own heads. It doesn’t do anyone any good - the more you navel-gaze the more you end up in a spiral that can lead to mental ill-health. The consumer society we live in thrives on this: the more unhappy we are the more we consume; happy people don’t tend to have this urge to consume. So the big corporations have all to gain from keeping us self-obsessed and miserable, and that counts even more for the tech giants, who need our eyeballs for their data scraping, than the classic, pre-internet corporations.

I’ve gotten to a point now where just looking at, interacting with and being in the world, brings me deep happiness and creates an urge to relay this which is irrepressible. I live in a perpetual state of wonder.

Eva Vermandel, ‘The Sky over the Southbank’, London, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

A selection of images by Eva Vermandel are published within issue 3 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

44. PRADA - A SPACE BETWEEN DESTRUCTION AND CREATION.

A series of artisan artifacts in LONDON.

Hand-stitched fringe dress with metal and crystal embroideries. Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

Borrowed utility jackets arrive - worn down, sprouting their internal waddings - modern trophy heirlooms - a life previously lived, the marred surface of belonging. Artisanally aged to costume a chosen reality, a series of identities offer a heroine’s wardrobe of perverse contradictions and intellectual complications.

A series of unlikely pairings flirt, never to be photographed by Lindbergh's lens, alas a delicious melancholia seeps - like Absinthe on flaming cubes of sugar - to be swallowed whole - a sweet liquor rush distilled to delicacy for a grown-up palette.

Canvases shrugged on over hand-stitched flapper fringe - hang by a thread, sway on bleached oak hangers - matte-ly porous and albino against a deeply pigmented patchwork of leathers.

Meticulous micro-metal and crystal-stamped embroideries disrupt a delicacy of textiles - abrupt close-up yet protected with perfected diamond shimmer from afar.

Hand-stitched nylon and leather bag - Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

A re-imagined replica of an archival Mario Prada bag tether an assortment of transcience, quietly signaling back to the heartbeat of a brand recognised for its DNA of the luxurious, the rare, and the symbolic.

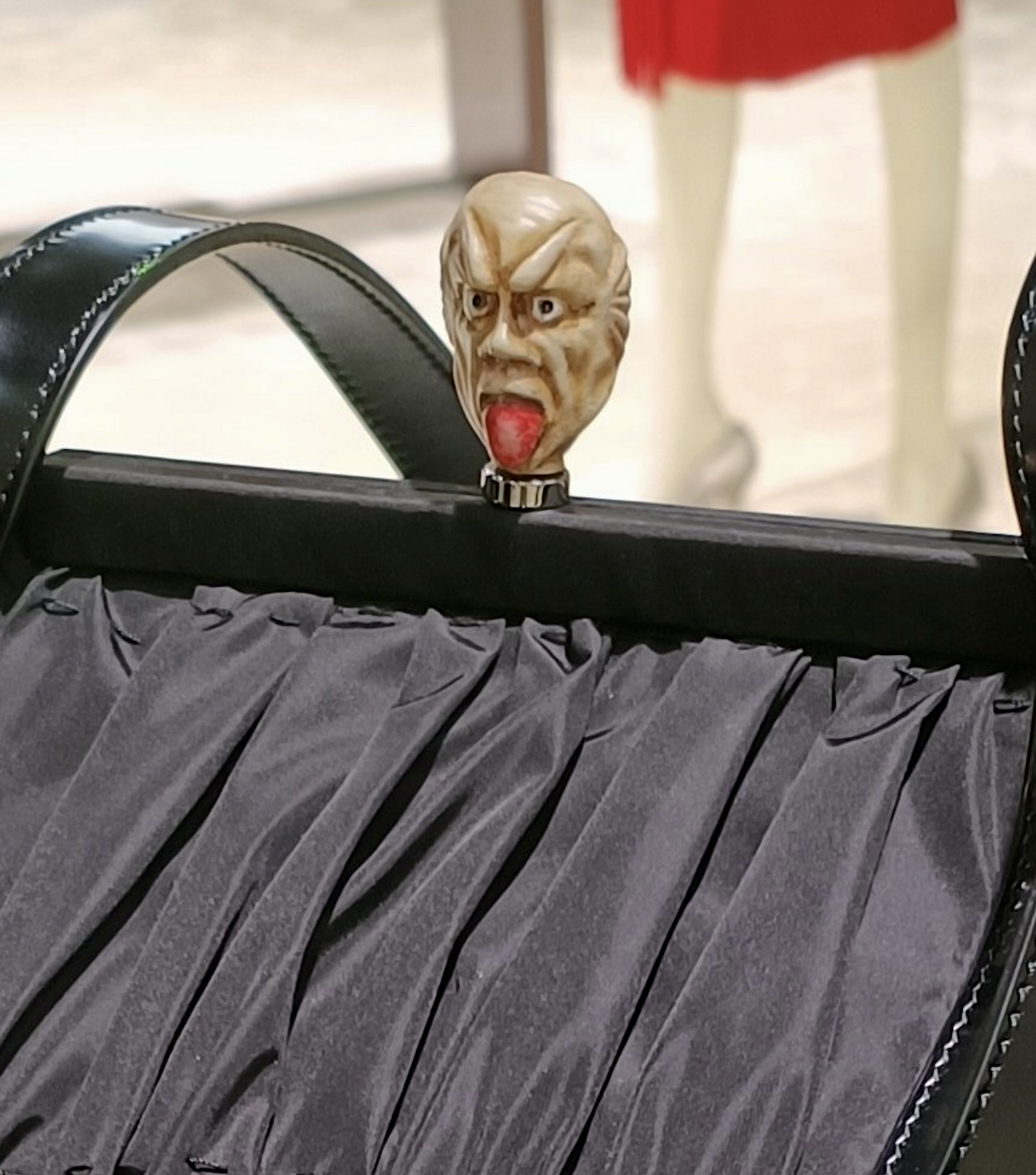

Originally in ruched and pleated black moire, now offered in feather-light, paper-thin nappa or signature nylon - snapping-shut with an ivory lock carved in the form of a satyr head - a direct resin replica of its original mimic the possible Japanese *netsuke origin.

An artifact, more talisman than mere decorative adornment, its protruding tongue and intense grimace remind and reflect back to an ancient - future punk - to destroy is to create.

The Satyr head - a possible netsuke object, originally in the possession of Mario Prada - replicated for a series of bag fastenings within the Spring Summer 2024 Womenswear collection - Prada.

Archival original - image courtesy of Prada X.

*Netsuke, formed by the characters 'ne', meaning root and 'tsuke' meaning attached - are highly prized, hand-carved micro objects originally created as toggle-like fastenings for securing the cord belts worn by gentlemen in 17th century Japan.

The Start Museum 111 Ruining Road, Xuhui District, Shanghai - until January 21, 2024.

Prada Spring Summer 2024 collection is available from January 2024.

Special thanks Rebecca Fletcher-Campbell, Edlira Panxha and Sui Zhonghua - Prada.

43. NACHO GAMMA - A SPACE BETWEEN LIGHT AND SHADOW.

The creative illuminates his personal process.

Nacho Gamma,“Carmine portrait”, London 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Framing the Light, was such a memorable performance piece, which came out of an extraordinary time, how do you feel now looking back at that work?

That moment helped me to give an end to a creative and personal block - by keeping myself active and not overthinking it helped me find again my path.

I, very often, return to that room through my memories. It is a way of leaving all kind of pressures behind whilst also bearing in mind the importance of following my instincts.

Nacho Gamma,“Framing the light”, Medium: sunlight, time and graphite, London 13/06/2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Nacho Gamma, “Framing the light (from 2pm to 10 pm)” Medium: sunlight, time, graphite London 13/06/2020

A sense of light feels so pertinent to your work, from those early iterations using natural light, to the portrait film with Oliver where you painted yourself in white, and then, of course, the symbolism of religious iconography which you return to, can you express why you return to light?

I have the feeling that the passage of time darkens us and that sensation used to worry me, because I had the impression that I was irremediably changing and stopping being myself. Now that I see life through a melancholic shade, I understand that, as it happens with the sunlight which transforms along the day, change is inevitable and looking at things from the darkness lets us see them brighter. That is why, for me, seeing the smallest beam of light has become such a unique event.

In fact, I find the limit between the concepts of light and shadow is something full of mystery that never stops surprising me. ¿How is it possible that two opposite elements need themselves as much to define their own existence?

I also find this duality in the relation between the human and the divine. A question which has not yet been resolved and has been reflected in our history through paintings, texts and monuments made by many other artists.

Nacho Gamma, image courtesy of the artist. From a series first published within issue one of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN)

Your contribution to the first issue of the magazine was extraordinary, I remember your commitment to that project and the images captured using your Grandfather's camera. The images from the chapel and the boards of visual prayers were incredible to see, please can you introduce that work?

The photos presented in the first issue are the consequence of a transcendental moment for myself.

Fortunately, before moving for a long period to Amsterdam and later to London my grandparents passed away. I mean fortunately because my fear was to experience this situation abroad and not being able to say goodbye to them.

After that, I spent two years abroad, completely distracted about what had happened. But once I finished my Masters and I returned to Spain I decided to go back to their house.

It was a harsh blow to find my grandmother’s chair empty after I opened the door, but it was then when I noticed that I could still grasp their smell still between those walls and I began to cry. It felt like they were still there.

Both their lives were kept in boxes and among all that I found my grandfather’s old camera and some photos taken by him. I immediately knew I had to give it a new life and that moment became a farewell I had never thought I needed until that very same day.

I feel that to define you in terms of media is sort of pointless, you are just so creative, and your contribution to the projects you engage with are so full - I appreciate that there has been an internal tension regarding working as a designer and working as an artist. How do you feel now about this point of view and what have you learned from processing that tension?

As a creative, I like to work in a space between fashion and art, where creating and expressing myself is the only matter. I believe that the set of projects I have been producing create altogether a spectre that fully defines me as a person and a professional.

That is why I despise it when I have to choose between referring to myself as a fashion designer or an artist in order to be understood by others and find a place in this society. When I try to fill the box is when I understand myself the least.

In fact, I do not believe there is any tension between art and fashion, because I believe they are the same, but rather on the relationship between my way of thinking and the constant fear of not being understood, because my work is born from the need of sharing.

Nacho Gamma, “Metamorphosis” presented at the city of Cordoba, at the international flower festival “Flora” Paniculate flower, wire and human body. Cordoba 16/10/21. Image courtesy of the artist.

The performative work you create is incredibly immersive, I always found that to be very impressive – do you find that you need to protect yourself emotionally in the exposure and creation of that work, do you have an alter ego that you engage with when you perform?

I am constantly trying to get to know myself better through my work. It is even a cathartic process I undertake to move on because by expressing my feelings and experiences I avoid any trauma contaminating me.

Performance makes me feel an adrenaline that brings me so much joy and makes me live with much more intensity. While the piece is activated, I feel I have the permission to act without thinking about the consequences.

It is very visceral. It is then when I feel authentic, so this makes me question where the alter ego actually exists, inside or outside the art piece.

Nacho Gamma, “East to west” Medium: snow and red painting for soccer fields. 10/01/2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your creative process seems to focus on the sensual, the tender, the body, from the works you have made so far, what do you feel you have learned in terms of your developing point of view?

I do not usually get a pause to reflect on what I have previously made because I am always thinking about what will be next, it is like a thirst that never stops. However now, when I look back, I can see a path that has come to life and I am proud of it.

What I do always bear in mind is that, in order to make something transcendental, it is necessary to stay truthful and consistent with oneself and that there is no better material than time.

Nacho Gamma,“Sunset at Trafalgar” Analógico, Cadiz 3/09/2020. From a series first published within issue one of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN). Image courtesy of the artist.

42. PHILIP GUSTON - A SPACE BETWEEN THE INTIMATE AND THE ABANDONED.

Philip Guston, Tate Modern - LONDON.

Philip Guston, ‘City’, 1969, Oil paint on canvas. The Guston Foundation.

From the wall of Philip Guston's easel to the infinite landscapes of his subconscious - which duly invite and reject.

Walking from room to room, the effect of retracing Guston is mesmerising - like following footsteps in snow which grow deeper as the man becomes the artist.

We see the many changes within a style, the many visual conversations and emotive sways of confidence, the trials and rewards, the tribulations and the risks which, viewed cold - seem to flush with the dreams and hopes of someone searching for himself. Reminding us all of the impossible - as the 66-year-old artist ponders at the exhibition end: 'I wish I was painting what I can now when I was 30'.

Losing elements and gaining space - how colour observed within earlier works return with personification in later paintings - renewed with a certain acceptance - As the width of the brushes increases with time, so too does the sense of freedom and immediacy, as if the time delay is narrowing to urgently communicate as the clock ticks on - speaking in a visual tone which turns from emulation to interpretation.

Ingrowing and internal, the works appear dazed yet unconfused, lighthearted yet focused - where a quivering gelatinous metropolis emerges as if from clouds of flour or icing sugar - freshly unmoulded and somehow distantly semi-translucent - as if brushing blancmange on table cloths taught over frames, using implements rummaged in kitchen draws.

A particular shade of aspic or tooth-paste-pink are semi-combined as if mixed in distraction and slathered on surfaces with a generosity of abandon - an effect which at first charms while also leaving the viewer a certain degree of nausea.

An atmosphere of cartoonish reality - where the landline rings, the neighbours argue and the sounds of the city below layer through the artist's open window - overheard in Americana colours, desperately upbeat and saturated in a platter of syrups shades which seem to dissolve to matt - thickly sweet yet tooth-achingly tempting.

Tears of the clown - distract the audience with a joke to protect from a truth which trembles with vulnerability - which the artist alone knows, and exorcises within a complex simplicity.

Guston's masterwork 'Flatlands' shocks with the heartfelt muffled thuds of a raining of objects - falling into a landscape, seemingly carpeted with snow. A spongey surface which catches each and every item with an evenness which feels unbiased even parental. Crammed into frame - a hurling of items, normally handled with care are seen in chaotic stillness - and yet, somehow viewed from the canine eye-line of the subjective - to thaw into the emotive and heartbroken - a clock's tick frozen in time - a violented moment caught-out, forever at 4:00, as the sun rises exposing a cacophony of exploded artefacts - once intimate now inanimate.

Philip Guston, ‘Flatlands’, 1970, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, USA) © The Estate of Philip Guston.

Philip Guston, Tate Modern, London - Until 25 February 2024.

Thank you: Anna Overden - Tate Modern and Neil Drabble for the recommendation.

41. CHIEDU OKONTA - A SPACE BETWEEN INTERACTION AND DISTANCE.

The artist discusses his creative process - LONDON.

Chiedu Okonta,“A 9JA Delta Speculative future”, acrylic and pastel on canvas, 2023, 91x121cm Image courtesy of the artist.

The painting you made of a figure in profile is fascinating, the subject matter, the symbolism, and the sense of the unfinished which is also finished... many questions here, please can you contemplate on your feelings towards this work?

Interesting question because I remember you saw the artwork before many people did. Actually, you saw the painting during its creation. My decision to create the art was to reflect a utopian reality which did not consider a realistic representation of what I hoped the Niger Delta region of Nigeria would be, but an idealistic representation of a feeling I hoped the Niger Delta would have. A feeling of hope and peace. It is a region plagued with insecurities, pollution, violence, and corruption. Where over presented materialism is seen as saviour and use of common sense as drudgery and propositions of cowards or preys.

The idea for that painting was never resolved from the start but started as a feeling based on the subject matter and body of work I was dealing with then. I allowed it to reflect the emotions in my personal life and in that sense, open to receiving as much feedback as possible. It held space for me to consider a topic that never seemed to get resolved, which was the exploitation and unethical exploration of natural resources in the region. It helped me to explore a space I was stuck in for a long time. Both the region and I needed room to exist from the financial anchors that seemed to prevent us from truly being free. A sphere that could repurpose everything to a healthier simpler form.

The background like a lot of my paintings told the story of the artwork. This time showing a rich surreal vegetation of a previously known garden city, which included structures rebuilt with minimalistic materials and unique identities. A young character faced forward, freely riding on a beach. It projects as a surreal dream, visibly expressed by the foreground semi-photorealist character. This character was vivid and present in permanent contrast. It wore minimal clothing as if about to swim or simply sitting in a domestic environment but also to reflect the freedom from the materialistic depravity that afflicted the region. The work evolved to present a character that was not thinking but more of a reflective wandering individual. Lost from the immediate environment and instead surrounded by thoughts, like a holographic 3D screen for projecting computer generated imagery. The character was also surreal and the only affixed part of my thought process behind the painting whilst the rest was in a process of revitalising healing motion. The painting was an expression of feelings and left to stay instinctive as you can remember.

How has your journey as an artist evolved?

I find myself in conversation always referring to my works as art. I have had to substitute art for painting even here. I used to draw and paint only. I plan, resolve, and then create. Now I start with a gut feeling of what I want to say and then I start sketching loosely leaving room for continuous evolution even to the point of “completion”. The medium I choose has become the best language for expressing an idea. I paint, I sculpt, I have enjoyed printing and installations. I create. However, there are mediums I prefer over others, mostly because of proficiency and factors such as the time available to transform the idea into matter.

I do love to paint even though I feel the medium is not always as important as the message and communication. Painting and drawing will always be special to me because of the pouring of visual images that come to mind and how fast I can put them down. I even see faces on inanimate objects and surfaces, which I mentally trace the outlines in the same way I draw. Maybe just a case of pareidolia.

I feel at ease now even if the work is not what I would in the past call complete or what my level of perfection was. Not important. I am comfortable to present the information and once I am satisfied, move on. Instead of the many unfinished pieces – as I called it- I have had to let go or just give out. I am more intrigued by what other practitioners do and constantly think of ways we can work together. It’s fun to see how I can continue evolving as an artist and adapting to the stimulus that courageously stands out to me.

Photorealism is extraordinary - literally extra-ordinary and in that space there is a certain new tension, a space maybe between technique and emotion - please can you reflect on why and how you use an image to express it?

Photorealism for me did not really come by choice. It came as a need to prove to those around me who mostly were not artistically inclined at all that I could show something that required more effort and precision over a figurative painting or drawing. Also, I would not really classify my work as completely photorealistic either. I try to get away from that and go beyond it. I do not want it simply to look like the picture, so I even make it flawed, leaving parts undetailed or humorous. I want anyone looking at my work to recognise the difference. In the past, I expressed the story and the emotion behind the piece with figurative loosely created backgrounds. A representation of what already existed, exists, or even surrounds you. While the foreground is a byproduct image or images you may refer to as photorealistic. I do this to create an interaction between the piece and the audience, urging and daring you to move past the vivid realistic foreground inwards to contemplate what strings and pulls together the value in the work, which is seen in the background.

Right now, I have come to the point where I am trying to create works that provide an emotional balance between the foreground and background and where possible create an illusion based on interaction and distance. A few artists I hold in high esteem have convincingly succeeded in doing that. At least in my opinion. I don’t know if that is how they feel, themselves.

As you have mentioned, for me it required a bit more patience, and in the space of putting in time you go through many emotions. A lot of impatience, a lot of stillness, waiting to complete sections so you can move on to more interesting and challenging parts, the frustration of time spent just to realise small noticeable changes, especially for anyone observing. You sit waiting a lot.

I remember running into you at The Anselm Kiefer show at The White Cube in the summer and we were both sort of dazed by how full-on the installation felt… which artists have inspired you and what work have you connected with recently?

Yes, Anselm Keifer’s “Finnegans Wake”. Astonishing exhibition. It is definitely one of them. The vision of the exhibition and the curation was overwhelming. It had a spirit that stayed with you. My mind kept going back to it multiple times a day for weeks after. It was sad, it was strong and heavy, however it left a glimmer of hope that was not tangible to hold on to or physically present but that you could taste. Very powerful exhibition. The medium he chose to use also had a profound effect on how I now see my choice of a medium as the most appropriate voice or language to tell the story. - How he used paint as the art itself and not just a medium to express the art.

Cinga Sampson: Nzulu yemfihlakalo was definitely another one. Photorealistic oil paintings are intriguing to me as the audience to interact with it. It had what I mentioned earlier, which was an illusion based on distance. I had been contemplating the idea for a while and when I saw his, I was very impressed with how he successfully pulled it off. Sokari Douglas Camp also because of her subject matter and choice of medium and how pleased I was to see how background and heritage could offer almost identical similarities in artistic ideas.

Julie Mehretu’s exhibition at the White Cube was another one I revered. It was a technique which was very innovative. The interaction between her creations and the audience was the art. Each layer of her work presents new information. Ken Nwadiogbu’s Fragments of Reality was thermal, heated, layered in mediums, and with the suspense of the journey’s been told. I have followed his career and have seen his growth as an artist.

I am drawn to the layers. How each layer of art creates a completely different part of the piece and how it tells a unique story on its own. A layer can be removed, and the art can still be presented on its own, but it aids in adding a separate identity to the piece.

Since writing these contemplations and interviewing artists I have really felt a point that connects each person - in the sense that each artist is at one with the media that they choose to express themselves - do you feel that you have a choice to be an artist?

A visual artist, NO. I never had a choice. For me it’s been about peace of mind. Even in my late twenties when I tried to run away from it and just be an engineer, I still could not. Visual art has been an element of struggle even though I showed an incline to it from an early age. It always seemed like something I was never supposed to do as a career or even at all. Out of sheer will and stubbornness, because I enjoyed it (and still do), I kept creating. Initially through drawings, then later paintings, now paintings expanded to include other forms.

This feeling of unease or struggle to keep art in my life is reflected in most of my works as a distant surreal realm or even dream-like apparitions. It usually serves as the impetus of the piece itself. Even now I could decide to be an Engineer with my experience and skill set but my very being continuously craves to be an artist. It has been an interesting interaction with the career of an artist for me. Like the dance between two black holes in the middle of a galaxy, coming together and then pulled apart. A world that comes and evades again. In between myself and me, Chiedu and Charles. Past and present become the present’s past again. A professional career which in the times I have held it, felt uneasy, unwelcomed, uncertain, and alien. However, this is the career part, never the art creation part. That stays eternal in and with me. My pursuit to become a career artist feels like a world constantly battling to remain unresolved but content.

A piece by Chiedu Okonta is presented within the RCA X HSBC - Across & Over exhibition - available to view until 29th February 2024.

8 Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 SHQ

40. DAWIT L. PETROS - A SPACE BETWEEN REFLECTIONS AND STRANGERS.

A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography, Tate Modern - LONDON.

Dawit L. Petros, Untitled (Prologue III), Nouakchott, Mauritania 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

The Stranger's Notebook explores geographical, historical, and cultural boundaries. In this series, Dawit L. Petros documents his travels from Africa to Western Europe, reflecting on a long history of migration. Passing through cities including Nouakchott in Mauritania and Catania in Sicily, Italy, the artist considers the migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers who make treacherous journeys between the two continents.

Petros photographs his companions and local people holding mirrors to the landscape, revealing reflections of coastlines, train tracks, and power lines. Conscious of his own position as an outsider in these spaces, the artist positions himself as a 'stranger', photographing his staged compositions from a distance.

Petros comments, 'For me, each of these journeys complicates Europe's status as an immutable historically and politically bounded space. I negotiated these journeys conscious that I came from elsewhere.'

Text extracted from wall didactics - 'A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography' Tate Modern 2023.

A series of works by Dawit L. Petros are presented as part of:

A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography Tate Modern, until 14 January 2024.

Special thanks to Anna Ovenden at Tate Modern.

39. GWEN JOHN - A SPACE BETWEEN WONDER AND WANDERING.

Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris. The Holburne Museum, BATH.

Gwen John, ‘The Convalescent’, c.1923, Oil on canvas, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Swept up and flushed in watercolor blush - lapsing into a swathe of cream paper - to retrace a moment of gesture shared between two - the model and the artist - the artist and the artist - yet inscribed for another, the collector and benefactor.

Rodin's brilliance in capturing charged transience crackles with a thunder unheard yet felt - an electrical currency that leaps a hip-notic landscape with a caress that condemns the inquiry of line to probable fatality. With each erogenous, ergonomic line - recorded through observation - tender in tracery - nuzzle the page with graphite grazes - as the gaze of a viewer discovers Gwen John. - An exposed intimacy in suspension - whispers and devastates.

Gwen John, Study for ‘The Brown Teapot’ about 1915-16. Oil on Canvas.

Burnt and raw, blunt paint strokes chip away the surface - an image sculpted with planes of light as if the foreground is faceted - out of focus while the viewers' gaze is lost in the background - the mid-tone tawny atmosphere of a time in the day where emptiness feels full (where adults work, children learn and the streets below are still) - where the light feels distracted - where the eye settles as if listening to the distant murmurings of a conversation in another room ...

The loaner in Gwen John - perpetual afternoon light and the tertiary shadow shades of a season in passing - lost and yet not found - where day follows day and night never falls.

The autumn's melancholic return with melodic purrs, fading in and out of consciousness in that specific way that Paris offers to those who still believe.

An impression - the listening and translated atmospheres felt with eyes open and doors closed - remembering a monochrome past - ebbing into a present still damp on the page - cautiously rendered as if moving forward in borrowed boots across powdered snow.

The instinct to express with the exhausted colours of a storm still on the horizon - a horizon of acceptance, glistening as if in a state of precipitation - leaving every surface mirrored into puddled emotions - pooling into ripples - the dérive abandonings and liberated wonderings of waiting for the rain to pass before choosing to succumb to a legacy drowned in grays.

Auguste Rodin, Nude woman lying on her back; arm raised and head hidden by drapery. c.1900. Graphite, with watercolour. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris. The Holburne Museum BATH - until 14 April 2024.

38. NEIL DRABBLE - A SPACE BETWEEN PROXIMITY AND INTROSPECTION.

The artist reflects on his work and introduces new book ‘CLOSER', launching at The Photographers’ Gallery - LONDON.

Neil Drabble, Untitled, (Playground), 2021 (from CLOSER, Double Obelus Editions, 2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

Your new publication ‘CLOSER’ views like a bombardment of empty urban spaces - all taken within walking distance of your home in London, can you introduce this body of work and why you are presenting this now?

Well, the series didn’t come from any pre-conceived thesis or prescribed idea – I wanted to move away from that and return to starting with making. I wanted to start without an idea and see what evolved. I knew I wanted to make something ‘local’, something ‘closer’ to myself physically and psychologically, but that was the initial extent of the plan.

Also, having made a series of photographic works in the USA and Spain as well as other places, I wanted to explore the potential for making work here in the UK.

I started walking – at night – without a plan and without a destination – the walks were all circular from my home, and all at night. There was something about working at night that also appealed to me visually and psychologically. The walks continued over a year period and the pictures evolved into the work that became the new book – CLOSER. The work ended up being made during the pandemic, but it’s not intended to be a response to lockdown – the main impact the pandemic had on the work was that the streets were very deserted and silent which I think helped me in the making of the pictures.

The statement for the book text nods to what the work is about – but having said that I never think that the pictures I make are about what they are of.

Within your practice and career you have engaged extensively with portraiture - what is it about this that interests you?

I was always interested in portraiture - as I kid I used to draw and paint people. I started making photographs of people as my way into photography. For a long time, I only ever photographed people - I taught myself photography through portraits - oddly, it was a long time before I started photographing anything else - seemed natural at the time, but my very early contact sheets are all people. The thing about portraiture is that unlike other forms of photography, it is a definite collaboration- it’s a two-way activity - it’s not necessarily an equal relationship, you are definitely in charge, and you need to be able to know what you are looking for and then you work towards that with the sitter. It’s a singular vision - arrived at by two people. When I embarked on Book of Roy (MACK 2019) - what interested me was the possibility of making a very extensive series of portraits of the same person, over a long period (8 years as it turned out). I had made lots of singular portraits of famous people (writers, actors, musicians) as editorial commissions - for these you have a very limited amount of time, and are usually aiming at one definitive portrait - with the Roy work it was the total opposite, a body of work where each portrait had to be definitive in its own right, but also work as part of a larger series.

Neil Drabble, Untitled, (Roy Red Hoodie), 2005. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your relationship with the US seems to really resonate within your work, what draws you back?

When I was growing up, America appeared as a very alluring and magical place – it seemed worlds apart from the dank and gloomy backdrop of 1970’s Manchester. The US TV shows presented teenage life as an endless Summer, where kids drove cars and went to High School Hops - whatever they were. In terms of photography, I think for people of my generation, this is where photography in the West evolved. As a self-taught photographer I learned from books (when I could find any), and they were predominantly American photographers usually focusing on landscape and portraiture. I guess it’s that thing of America being the mecca of some sort - the home of the image. Also, visually and semiotically it’s similar to the world I grew up in, but also different, which allows different possibilities to make work there. The signs and symbols are recognisable, but don’t come with the same social and cultural baggage for me as similar things would do in Britain. There’s also much more of it to explore. The initial shock of actually being in America eventually wears off, but there is still something that draws me back to it. I guess one of the reasons Book of Roy evolved was due to my desire to make a body of work in the USA.

Neil Drabble, Untitled (Tyre Tracks), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your portraits of trees are fascinating, they are a subject that you return to again and again, why is this?

I’ve always enjoyed trees for the way they make me feel.

They have the ability to elicit and suggest the potential for emotional resonance that inspires me to return to them as subject matter.

They’re also amazing kinetic sculptures, moving and changing with the seasons. They’re everywhere so it’s a subject matter that I can work with across global boundaries - they speak to people regardless of the language.

Neil Drabble, Untitled, 2000. (from Tree Tops Tall, Steidl/MACK, 2003). Image courtesy of the artist.

There is a historical relationship between artists also being educators, both within the work they physically make and also the work they contribute in terms of teaching others. We have discussed this at length and I remember you saying how you felt that everything in some way is part of the work, can you expand upon this?

As I said, I’m self-taught and didn’t have a great educational experience, so becoming involved in teaching was not planned - it sort of happened. A good friend kept asking me to do a guest lecture for his students, but I wasn’t sure about it - I eventually agreed, and was very surprised by how much I enjoyed the experience, how much the notion of ‘teaching’ seemed to have changed from when I was at Art School, and how much I enjoyed interacting with the students. I then made it my mission to become more involved with teaching and ended up teaching on various courses. I always saw the teaching as part of everything else - everything you do feeds into everything else - one thing that did happen was that in having to explain things to students and give lectures and tutorials, it helped me to access a dialogue with my own work and motives that had previously been on a more subliminal level. Verbalizing things to other people is a very good way to make you think about what you are trying to say.

Neil Drabble, Untitled, (Sidewalk Sun), 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

The image of the sun drawn in the concrete, published in issue 2 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN), is such a pivotal work within the magazine - It says so much about the time we are in, and feels so optimistic and yet so sad at the same time, please can you tell me about this image?

The picture was made in Los Angeles for another project I’m working on. I work quite quickly and respond to things either emotionally or not. This picture seemed somehow, as you say, to straddle between being optimistic and melancholic – which I think runs through the majority of my work – in this case, the ‘up’ was ‘down’ – the sun was up, but it was down on the ground.

To purchase CLOSER, click HERE

Book Launch & Signing, Neil Drabble: CLOSER 02/11/2023, 6:30-8:00pm. The Photographers Gallery,

16-18 Ramillies Street, London, W1F 7LW

37. HIROSHI SUGIMOTO - A SPACE BETWEEN THE SKY AND THE HORIZON.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, Hayward Gallery - LONDON.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Tyrrhenian Sea Priano, 1994.

When I go to a mountain,

I feel some kind of spiritual experience,

as if a mountain's spirit enters my body,

this spiritual experience led me to wonder -

where do waterfalls go?

My answer was the sea.

H.S.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, The Hayward Gallery Until 7 January 2024.

Special thanks: Megan Edwards at The Hayward Gallery.

36. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ - A SPACE BETWEEN WAITING AND RESPONSE.

Marina Abramović - The Royal Academy - LONDON. Notes from an exhibition.

Marina Abramović - A photograph of ‘The Artist Is Present’, 2012, performance piece, New York.

Marina Abramović - A photograph of ‘The Artist Is Present’, 2012, performance piece, New York.

Faced with focus - interconnected gazes, lines of sight, inside the eyes and out,

empathy - across a room - digitally re created - re-lived from a live recording.

- invisible like a laser, the signal - the sight detected at either end of the invisible.

'The Artist Is Present'.

The artist appears to be searching, studying the face of the viewer, one at a time - zeroing in - whose collective expression seems 'open' to those eyes.

Seen en masse from an inexhaustible camera recording every blink, looking down while the viewer looks ahead - focused and unaware of the constant documentation. the sitter is zeroing out, the camera focused in.

The artist's face - a Madonna, eyes wet exhausted glazed gaze - a line sustained from room to room, looking out looking in - as the flickering images change the atmosphere retains and remains - spaces that occupy an all-encompassing conceptual consideration.

The pencil sharpener of the father presented in the debris of life validations - of images and medals, placed, status with stationery. Stationary status. Stationary stationery.

the sense of waiting -

waiting on a white horse, with the white flag, without charge.

the fashioning of an artistic identity

the fashioning of heroism

the fashioning of martyrdom

created chaos

a sense of distance - the construction of a point

presence of body and without a body

Silhouette impressions of jars - enormous vessels - black mirrored, glazed, inverting a room in their reflection, meeting in the middle of the Great Wall of China - to conclude - a closing ceremony.

A crystal portal - mineral projections - to pass through a needle. a doorway to another space.

Mathew 19:23-24 … it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.

Faithful furniture - heeled in crystal - to touch the floor en pointe.

A church room, the threat of penance, the ladders of knives.

impossible realism.

the elongated limbs of the simple - seemingly humble, and yet architecturally conducted - churches without spires.

Minimalist yet maximal - contradictory in impression - the crystals positioned like talismans to protect - and yet - protection is exposed like the weapons of surreal function - ladders to climb to sever and to return to prevent - the function of prevention.

Searching for personal order within the created chaos of control.

The invisible collaborators of a studio, an orchestra of parts - the technician, the filmmaker - the carpenter - akin to the untraceable line of eye contact in 'The Artist Is Present'- the support of the maker allows for the work to function outside of a room set for the mass - the fashioning of such illusions.

The space left within the simplicity of presentation allows for the discomfort of sophistication which provokes a certain nothingness that is neither acknowledged nor defended. To accept like a religion - which the artist actively engages within and uses to stabilise - a Madonna whose presence is felt - even feared - we do not know the values of this world order - of processing - as the faintly heard throaty yells blur with the electrical whirrs of mechanised projections.

A retrospective of retrospection.

Marina Abramović Royal Academy Until 1 January 2024.

Special Thanks: Jessica Armbrister at The Royal Academy, London.

35. ZHONGHUA SUI - A SPACE BETWEEN EFFORT AND DETACHMENT.

The artist contemplates his creative process.

Zhonghua Sui, Image courtersy of the artist.

The portrait of the character, dressed in a chinoiserie bomber jacket, blankly looking directly at the viewer, in the middle of Regents Street with a rail of copied garments is such a pivotal image within your body of work - the implied symbolism of ethical tokens provokes the image as high art to me - can you discuss what the image means to you?

When I saw this enthusiastic guy approach and celebrate, taking on the role of a fashion model interacting with the installation, we together created a miniature fashion tableau. To me, it felt like a celebration, with the performance of a fashion model strutting out of the bar, dressed in fancy attire for a glamorous date, and the emotional tension when facing the camera: the mix of nervousness and relaxation, the alienation of relationships between people had all manifested in this miniature spectacle.

Zhonghua Sui, Image courtersy of the artist.

Zhonghua Sui, Image courtersy of the artist.

Thinking back to your work where you repositioned garments into stores... I found that to be unbelievable and yet when you presented the work it made total sense... can you explain the circumstances around making that body of work?

This is my process for "appropriation" in the fashion industry, using degradation and transformation as means. I purchased some typical essential clothing items from various commercial locations in London and brought them back to the studio. I then meticulously replicated these garments following their patterns, using recycled industrial sails, while leaving oil stains representing labor participation during the production process to reveal the true face and cost of a piece of clothing.

Finally, I returned these degraded substitutes to the original packaging and the store of the original brand, making the fashion consumers in the store my first audience. When they returned to the shelves and became part of the neatly arranged products for sale, they easily caught the customers' attention due to their uniqueness. The only regret is that I politely refuse people who love them because they were "not for sale."

I remember the moment when you received an excellent grade from The Royal College of Art for your degree work and you said that you felt underserving of the mark - your values are very connected to the structure and interpretation of public systems, why is this?

I believe that my practices are a gift from society, and I just discover and document them. I enjoyed the discussions we had at RCA about the path "Humanwear," where a good society can define excellence, but being defined as excellent as a human still makes me feel fearful and humble. On the other hand, the field I care about has never burdened me with the weight of elitism. When I see so many people working so hard without achieving results or no conditions to make an effort, makes me approach excellence with a sense of detachment.

There is a performative aspect to your practice that is really fascinating, the act of making, constructing, and the act of observing, why does human behavior interest you?

As a society practice with uncertainty, my work became the subject of excessive praise from many passersby as I moved professionally along London's Regent Street, even though all of these clothes came from the fast fashion industry.

What's interesting is that the pure white installations representing labor participation, transported to the consumer center, became the focal point of the spectacle and interaction. They were enveloped by the sparkling streets and crowds, but in photos, they often appeared ignored, seemingly less important, with people turning their backs to them.

I wanted traces of audience participation in shows. I once had the audience exchange coats with performers, inviting the audience to play the role of assembly line workers folding origami clothes. Each participant left fold marks and fingerprint traces that were quite uniquely elegant.

This meant that everyone's practice had a compelling story, one that we had never seen or cared about, much like those clean and tidy ready made clothes. I was captivated by grand narratives and the collective unconscious from a young age, but caring about and understanding real individual people as my act of resistance is particularly important to me.

Responding to instinct is something that I really respect within your practice and in conversations which we return to... and yet I wonder, do you need to somehow separate yourself from your art practice and your work as a human, because to be an artist who so directly questions - must be personally very provocative.

If my work still remains as a gentle opponent in everyday life, then I aspire to engage with real societal processes, not just the act of creation itself and the pleasurable emotional experiences. Society being possible, through establishing dependencies and recognizing each other's rights. What I hope to do is not to expose consumerism as a demon but to acknowledge the significance of cooperation in the process of recognizing rights and interests. Long-term certainty and optimization are my goals, rather than confrontational moments. Therefore, artistic practice and the artist themselves can coexist without conflict. I prefer artists to have a business acumen over what businessmen do in the name of fashion.

Joseph Beuys' thoughts that all humans are artists is conceptually so timely, what do you feel about this idea and do you believe it to be true?

I am interested in appeals that emphasize the class of people. I would think it as the power of interpretation in art returning to the hands of individual, where information flattening makes individual expression a form of artistic language. However, what concerns me is that when the boundaries between art and life are blurred, a weary resistance may arise to avoid the ostentation of the fame and the violence of political life. In fact, art is an eternal presence in human social life, and the eternal violence on the path of truth, as well as social events, inevitably need to be experienced.

Zhonghua Sui, Image courtersy of the artist.

34. RAMI EL ZEIN - A SPACE BETWEEN DARKNESS AND RELEASE.

The enigmatic artist discusses his creative process while introducing a film made from memory.

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

Please introduce your film Threaded.

Threaded is a short animated film about concealed identity and cultural and familial expectations of a young Arab man called Faisal. It follows a dark chapter of his life where his secrets are revealed as well as the consequences he suffers. The story is told from his mother’s perspective. We hear her version of the events whilst seeing everything unfold from his side.

Your use of the rotoscoping animation technique within your film is very affecting, there is an amazing sense of depth of emotion captured within your line quality, how did you decide upon this technique and why do you use it?

I’ve been using this technique for almost ten years now and I love it for the exact reasons you mentioned. It allows for the emotional depth to really peak through. It makes you realise that although we are in an imaginary animated world, the story stems from real life. It adds a sense of realism and documentary effect that you can’t really get from other animated techniques. This is the first time I have used digital oil paints. And although it’s a very lengthy process animating frame by frame, I’m deeply enjoying it. It’s such a rewarding experience when you see the clips playback.

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

You have lived in different countries, with very specific cultures, what have you learned from each place you have lived in and how has this influenced your work as an artist?

I think living in different countries made me realise that it’s ok that I don’t belong to any specific culture. Because I don’t feel that sense of belonging, I focus more on what connects us all emotionally. That’s why I lean into family dynamics and generational trauma in my storytelling. Because these are topics that the audience can identify and connect with. For many people watching a film between a parent and their child, they can understand that connection regardless of where and when the story takes place. It sounds simplistic and obvious but I do think there’s something powerful in that.

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

The use of darkness as an atmosphere within the film, seems to engulf the characters, the depths of tone seems to wash over the subjects... what is your relationship with darkness within 'Threaded' and can you expand upon your decision-making process to create spaces which seem so expansive and yet undefined?

Because of the dark subject matter, it was important for me to hold back from anything decorative. Some scenes are coloured, some are in black and white. As you watch the film, you will notice how the different timelines look aesthetically different. Every colour in this film is deliberately chosen to evoke a message. Because this film also explores memories and the retelling of events, the darkness around the characters allows us to focus on what is essential in the scene. I am also showing the suppression that the main character is facing.

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

Freedom of release is something that connects all artists - what do you want to release with your film 'threaded'?

We’re living in a world where hatred and persecution are on the rise around the world. Violence is everywhere whether it’s the refugee crisis, climate change, the agenda against the LGBTQIA+ community etc... I think anyone who is paying attention today is feeling a sense of dread of what’s coming next. My films have always been a means for me to process those feelings. Particularly when I’m drawing frame by frame. That’s my release...

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

Film still from ‘Threaded’ by Rami El Zein, courtesy of the artist 2023.

33. AIMILIOA METAXAS - A SPACE BETWEEN DESIRE AND DAYDREAMING.

The emergent artist discusses his creative process.

Aimilioa Metaxas, 150x190cm, Ink on canvas, 2023.

There is a quality of levitation within your works, a state emerging between different times... something ancient and future simultaneously seen, can you reflect upon time within your work?

I think is very important to look back on the past to reflect, as long as you don't forget to keep your focus on the future. You need to remember that you can't change what happened in the past, but you can always influence the future.

The past plays a fundamental role in our evolution as human beings. We get the chance and absorb all the knowledge our ancestors dedicated their whole lifetimes to discover and allow us to use this knowledge to advance our ways of living. For me the past, my roots and heritage play a fundamental part in who I am. I grew up in Greece, the myths and art of the Ancient Greeks had a permanent presence in my education, life and upbringing. Because of that, I use characters from old well-known stories to share my ideas and thoughts to discover more about myself.

I found your mention of an ancestral link to silk to be really interesting and how specifically you feel towards not framing your works with glass, please can you expand upon this?

In the digital age, we might have the opportunity to see more images than anyone ever could, but we became blind to the materials that people use in order to create these works. It is important to remember that throughout history the materials themselves were meticulously chosen for each piece and added character to the works, hence it is vital to understand the role the materials played as fingerprints to the artisan's labor, as well as a testament to the time and place the piece was made. From the famous ultramarine to the coveted Tyrian purple, to silk and gold - all these materials add a distinct feel that cannot be experienced through our phone screens. That was one of the ways I protested against the craze of the digital age. I created works using ‘luxurious’ materials which forced people to come and see my works in person, that way they have the opportunity not only to see my works in a different light - from how they would if they saw them online, but also get the chance to interact and exchange ideas with other present individuals. Silk in particular is a material I experimented a lot with in my latest works. My last name is Metaxas which means silk in Greek. The story of my ancestors is that they used to export silk from China to the Byzantine Empire through the Silk Road. I grew up with silk, as it had a permanent presence in my childhood from the stories I would hear about my ancestors to the myths the ancient Greeks wrote, silk has always been this magical material that everyone desired.

Aimilioa Metaxas, 70x70cm, Ink on silk, embroidered pearls, 2023.

The reason behind my decision to not place a glass frame onto my paintings is to avoid the separation that it creates between the art and the viewer. Glass as a material is cold, distant and unbendable. Our daily lives have been conquered by seeing everything through a glass frame, creating a barrier between ourselves and our experiences. I wish for people to become closer acquainted with my works, to be able to see them not only through sight but with the sense of touch. I feel that as people crave more intermediate connections, for a sense of touch, a true experience which has been lost in the last few years. Throughout history, humans have experienced life using all of their senses, sight, touch, hearing, smell, etc. We recently lost touch and we wish to get it back.

The symbolism within your work feels very strong, can you expand upon your instinctive connection to the symbolic?

For me, symbolism serves as another form of language. We use symbolism to express our ideas and thoughts when it’s difficult to do so with words. Each image could carry a whole sentence within it and so you could say my paintings can be perceived as texts written in the symbolism language. It’s a way for me to bring forward personal dilemmas and to question the world in which we live. Furthermore, my fascination with mythology and storytelling, fashion, and jewelry, plays a huge part in fuelling my curiosity about how people used symbolism to convey messages and have full-on conversations with no words needed to be spoken. It serves as a testament to the genius creation that we humans are.

You react to events in a very considered way, as an artist what do you feel your work explores and what is affecting your creative responses?

I feel a strong desire to influence people and assist them in dealing with their inner demons. I do believe that finding a balance between living life as an adult while keeping your inner child alive is vital for one's survival. Balancing desire with innocence, responsibilities with daydreaming.

In search of inspiration, I would often go out to meet with people and create my own experiences. It is important to have your own real experiences if you wish for your work to be sincere. Nothing can replace the impact of experiencing something yourself. Humans are at the center of my work. I explore identity through the use of mythology and the depiction of the human body, in addition to how everything is being influenced by the idea of value that we humans have artificially created.

The works often seem quite visually threatening and yet there is also a playful tension that you explore. How do you decide upon the context of your paintings?

Life is all about balance. As the saying goes, for all the happiness you wish for someone, someone else gets cursed with equal misery. Honesty sometimes can come across as threatening or scary, desire and lust cloud your mind and actions. At the same time, though desire is the leading cause for innovation, exploration and knowledge. Playfulness serves to balance these forces of nature, to restrain their destructive nature, and reveal their potential.

Aimilioa Metaxas, 190x150cm, Ink on canvas, 2023.

Aimilios Metaxas - Utopian City - until 13 September 2023. Artsect Gallery, Algha Works, Smeed ROAD, London E3 2NR.

Riposte Day Rave - Saturday 16 September 2023, 12:00 Noon. 60 Dock Road, London, E16 1YZ.

32. ODOTERES RICARDO DE OZIAS - A SPACE BETWEEN THE ALTAR AND THE ALTERED.

David Zwirner, 24 Grafton Street - LONDON.

Odoteres Ricardo de Ozias, Que Perigo!, 2000, Oil on hardwood board, © Danielian Galeria, Courtesy Danielian Galeria and David Zwirner.

While Londoners left the city in search of sun this summer, a mass of paintings, bright with the light of Brazilian artist Odoteres Ricardo de Ozias (1940-2011) arrived. Seen for the first time in the UK - at David Zwirner's Grafton Street townhouse gallery, awaiting exhibition from the 1st of September.

Invited for a preview in July, I entered a room, white like a fresh sheet of paper, while an unboxing of paintings was in the process of being propped against the walls ahead of installation. Post-it notes colour coded three themes, agriculture, religion and carnival. As I listened to curator James Green introducing the works, I soon began to appreciate quite how extraordinary and contradictory the paintings on display are.

What appears to be a series of landscapes painted in a childlike, naive style take on an entirely different context when you realise that the works on display, were painted by someone in their fifties and sixties, who only began to draw at age 40. The decision to present this work, in this gallery at this time is conceptually fascinating.

Ozias presents a technicolour vision of a life in review - as if released from possession. His primary palettes clash in saturated celebration and heightened state contemplation - so much so that viewing in silence leaves the viewer deaf, only to hear your heartbeat pound - there is a noticeable colour of understanding that is unsaid yet implied - shades of joy, violence, repression and hysteria.

The mind whirrs for references, for visual clues and reason, but Ozias's genius seems to repel the reinterpretation of others - the works exist outside of the studied chapters of art history - his coded outpourings are a release not made from external sources but from internal processing - the intensity and rhythm of his paintings - concentrated to a hypnotic, teeming focus, suggest of a searching meditative approach to creation which provided catharsis to an individual who for the majority of their life worked hard within the mechanised systems of others.

Odoteres Ricardo de Ozias, O Coro, 1999, Oil on hardwood board, © Danielian Galeria, Courtesy Danielian Galeria and David Zwirner.

The previous owner of the works Lucien Finkelstein (1931–2008), amassed a six thousand piece art collection within his lifetime, holding one of the most important independent collections of naïve art, a term initially used to describe the work of French self-taught modernist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910). There are intriguing parallels between the visual style of the two men, both seem focused on a sense of anticipation within their works, with Rousseau's flat tigers and reclining nudes proposing a cardboard cutout of sensationalised terror, Ozias moves further depicting an enclosed pool of crocodiles decapitating a sunbathing onlooker. As with both artists and a generalised observation of naive art, it is the subconscious that is prioritised over the continuous.

The momentum surrounding the exhibition builds as you walk the room, looking into each rectangle like stills from a silent animation, their bold flat colours immediately entertain and then as your eye falls on the miniature details, intricately indicating that not all is as it seems.

Growing up in rural Brazil, a small town named Eugenópolis in Minas Gerais, he worked with his family as an agricultural labourer aged five, leaving the countryside and relocating to Rio de Janeiro at age twenty to be a Mason, before working as a station agent at the Federal Railway Network. Some decades later he is office-bound, working as an administrator due to health problems. It is here, exposed to stationery supplies for the first time that he begins to draw, papering his office walls with caricatures of his colleagues. He is then commissioned by his employers to illustrate a book of Amazon wood species, published in 1981 - and for the first time, Ozias is presented as an artist. The origins of a diagrammatic style created with the tools of a conceptual thinker continue to be employed throughout his career. Found and foraged implements are favoured over traditional art supplies, Formica offcuts form his canvases and industrial gloss his pallet. While the techniques employed as an agricultural labourer and industrial mason possibly influenced the construction of his paintings, where a scene is formulated like a stage set of layers, scenery and players perfectly placed for the gaze of the best seat in the house.

The paintings on show (1996-2004) are from the period the artist was also an Evangelical Minister in the Pentecostal Assembly of God - a context that seems irresistible to connect to a prolific outpouring of works that often frame a central figure, a compositional structure like the altered pieces of an altarpiece.

The artist's introspective searching and questioning is palpably strong when considering the thought that some of his evangelical community rejected his artistic practice with a religion marked by rigorous traditionalism and fundamentalism - opposing the visual depiction of any living beings or religious figures. Knowing this makes the life of Ozias even more fascinating. - The creation of 400 known artworks before death and to iterate without repeating nor edition - all consistent and self-managed as if responding to a private brief removed from sales, concept or fame rather a meditative state of prayer.

Odoteres Ricardo de Ozias, Ala das baianinhas, 2001, Oil on hardwood board, © Danielian Galeria, Courtesy Danielian Galeria and David Zwirner.

Odoteres Ricardo de Ozias - David Zwirner 24 Grafton Street, London - 1-29 September 2023.

Special thanks: Sara Chan and James Green.

31. JOYCE ADDAI-DAVIS - A SPACE BETWEEN CONFRONT AND CONCEPT.

Changemaker Joyce Addai-Davis discusses her radical design purpose while exposing a truth we all need to know now.

Joyce Addai-Davis photographed in front of Old Fadama Landfill, Accra Ghana. Photographed by Nii Ayi Lamptey (Nii Ayi Visuals), 2023.

‘Who is in my community? Anyone who wants to navigate life without destroying the earth.’ Joyce Addai-Davis.