132. GEORGE CONDO: A SPACE BETWEEN ARTIFICIAL AND REALISM.

George Condo. Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris - PARIS

George Condo, Untitled, 1998, Collection de l’artiste. Photo: Courtesy Studio Condo © ADAGP, Paris, 2025

M-A: ‘George Condo’s mass of hybrid paintings, overwhelm as to be tainted with the stains of consequence, both ancient and future. Irritate the very essence of now.’

Paintings as drawings and drawings and paintings - his particular jarring of image - make for an active riot of fetishised depictions of violated bodies.

Akin to Philip Guston - whose tremulous paintings quiver with frenzied trauma - Condo is near carnal in comparison - obsessive of flesh - his primal depictions arc through emotional intrigue, at times wanton and macabre, at others surprisingly tender and yet consistently volatile, in composition and nuance.

As a tide, we return to the condition of man, the fundamental frustrations and release - as within the states of consciousness - we see the wrestling and resolve of an artist aligned to releasing an instinct to line - that is both mysterious in nature and rehearsed in nurture - asking the question; what is George Condo unearthing within works which seemly fixate on a surface, salacious to shock.

His expanded canvases have no central point of focus - a pictorial language of self-proclaimed 'artificial realism' - challenge notions of morality and freedom - as to watch stilled cartoon content caught between channels - outlawed as amusement - an inferno of confusion - as his hacked and torn collages - form plateaus - as the debris of an abattoir floor, familiar in anatomical form yet fractured in proposal - works appear as undulations of tone - as to be seeped in fluids of life no longer active yet fermented in genetic information.

As carved into canvas - a sequence of works further resist categorisation - part notation, part visual score, he further toys with definition - antagonising historic positions. Bleached canvas drawings appear gleaming - their inscribed surfaces pressed with information as if platinum sheets. Layer upon layer of a filigree of some ancient inscription - expose a crawling surface of the grimacing - as to scan the inky pages of newsprint - subconsciously seeking - chance forms within the spaces of white - a scrawling codex of rhythms running backwards and forth - forming a patina to mar - to exhaust into continuum.

George Condo, The Cloud Maker 1984, Collection de l’artiste, image courtesy Studio Condo © ADAGP, Paris, 2025.

GEORGE CONDO Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris - Until 15th February 2026.

With Thanks to Eléonore Allier

131. PAUL MPAGI SEPUYA: A SPACE BETWEEN WITHIN AND APART.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2070386), 2017, 24 x 32 inches. Courtesy of the artist, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

‘…the mirror is overall a device that creates a boundary between subjects or objects and viewer. They draw the line at what is within, and what is apart. What I like about this is what’s left is desire as a method of navigating this boundary.’

Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

To see a work by Paul Mpagi Sepuya is to enter an atmosphere which appears conscious of our gaze.

Billboard in scale, his life-sized figures, often staged within swaths of curtains, evoke a protective set - a space of improvisation, careful to record the pivotal in the play.

As to be conscious of a position held by others and to embody a tender curiosity which exists on the very edge of instinct.

Seeing your work at Paris Photo was revelatory. A monumental image - the two figures gently holding each other, the asymmetry of composition, the sense of a stage within a space which seemed poised and yet ambiguous, and the scale - as a 17th century European oil painting... it was extraordinary to witness within the Grand Palais, a space filled with activity and noise and when I saw your work - sudden silence.

Thank you, it’s always nice to hear how people encounter my work for the first time.

Twenty years into this, and about a decade into the work that really came to be known to wider audiences, it’s helpful and good to know how what to me feels so familiar does appear to new eyes. The title of that work is Daylight Studio (0X5A4577), from 2022. It’s from a series from Spring 2021 through roughly Fall 2023 called Daylight Studio / Dark Room Studio, which was a follow-up to my 2016 - 2021 project Dark Room, that explored play and intimacy within formal construction and deconstruction of my studio and the space of the photographs through mirrors and other elements. This new series was sparked by moving studio spaces, and in the process of settling in, looking at historic images of Western European and American photography studios. I began noting at first, and gathering objects - antiques, postmodern and contemporary pieces - to inhabit a kind of historic but resonant space. I began photographing myself alternating between working or preparing the space and resting, or napping, and then as COVID opened up, inviting friends in. This is a rare photograph made with someone I met that same day. Vonnie asked what I did I explained this project and he asked to come by and take part. I’ve mostly resisted photographing at-the-time stranger for many reasons, but these pictures really came out thanks to his curiosity and our playfulness.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Daylight Studio (0X5A4577), 2022, 50 x 75 inches. Courtesy of the artist, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

The veiled spaces really fascinate me…

Maybe I’d describe this as nested spaces within the photographs that contain something being looked at or reflecting that the viewer of the final image cannot see. Every backdrop divides a space into what’s between the material and the wall, and then what’s behind it. I was just curious about that space. But there are very few veiled spaces, except maybe in the “SCREENS” works. There are backdrops that serve as dividers, there are mirrors at angles. There is the camera that obscures a subject’s face with its own reflection.

Observing the images, I was fascinated in the sense of a surface as witness - the occasional smudged fingerprints, the tawn tapes - fragments of the temporal... all form a sense of being held and a sense of touch, the focus on hands but spaces which seem to hold time... can you expand upon how you use space and ideas of space within your practice?

Yes, surfaces have been a major formal and conceptual aspect of the larger DARK ROOM project and the project that followed in Daylight Studio / Dark Room Studio. In many of the pictures, what you are looking at is a photograph made of the surface of a mirror, which includes reflected the camera making the picture. The photographs shown at Paris Photo Voices are all “direct” pictures as in they are not of reflections, but in each there is a mirror present that provides to the figures their reflection to engage with. What I’m interested about with these is that there is a closed loop, a circuit happening between the subject(s) and their images that is not visible to the viewer of the final photograph. A hidden intimacy there.

The returning use of reflections feels more of a gesture within your work than a direct object, even when mirrors are utilised. This really interested me, how through movement and observation, you explore a sense of return. A feeling as a echo which at times feels like a time delay... Please can you contemplate the use of a mirror within your practice?

The use of mirrors began in 2014 with initial Studies, a series of photographs using them as surfaces on which to affix unresolved image material and notations, creating formal arrangements that would only come together and be photographed through the point perspective of the camera placed on a tripod in front of, facing the mirror. I realized that its surface should not disappear so that it’s presence could be noticed. It was not meant to create a trick. So I stopped cleaning the surface between photographs and smudges developed. The DARK ROOM project began when I was experimenting with new portraits while using backdrops in my space, and it caught my eye that when reflecting these black and brown fabrics, the otherwise latent smudges and fingerprints came into clear view. This opened up so many metaphors and ways of thinking. But the mirror is overall a device that creates a boundary between subjects or objects and viewer. They draw the line at what is within, and what is apart. What I like about this is what’s left is desire as a method of navigating this boundary. A desire to be in relation, or within, when realizing the space into which the viewer is looking is actually closed off, despite the camera’s reflection seeming to implicate them.

Your work evokes an ongoing exploration with collage and collaged conditions, which enable such an idiosyncratic state of poise. Similarly to an earlier thought about gesture, I am fascinated by how you verbalise states visually. How do you know when you have reached a point where the work evidences how you feel?

That’s an interesting question, I’m not quite sure what you mean. The original “Studies” from 2014 - 2016 were temporary compositions for the purpose of making photographs that in turn looked like collages. Each was a response to the idea of a portrait of a person or persons close to me. So within them there is a kind of longing, missing, or wanting and desire. In the “DARK ROOM” series Mirror Studies that also were described as collage-like, they work for me in the same way. Later *actual* collages that I began making in 2018 were more about looking at composition. But all works for me have some nested sentimentality. But it’s a funny question because I realize I’ve never considered an evaluation of the work based on wanting the viewer to feel emotionally. Or about communicating anything about that on my end. What I want the viewer to feel is themself in relation to pictures and material that they are outside of, excluded from formally but implicated in relation by way of their own desire.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, DARKCLOTH (_2000142), 2016, 24 X 32 inches. Courtesy of the artist, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

130. GEORGES SEURAT: A SPACE BETWEEN POPULOUS AND LONE.

Radical Harmony, Helene Kröller-Müller's Neo-Impressionists. National Gallery - LONDON.

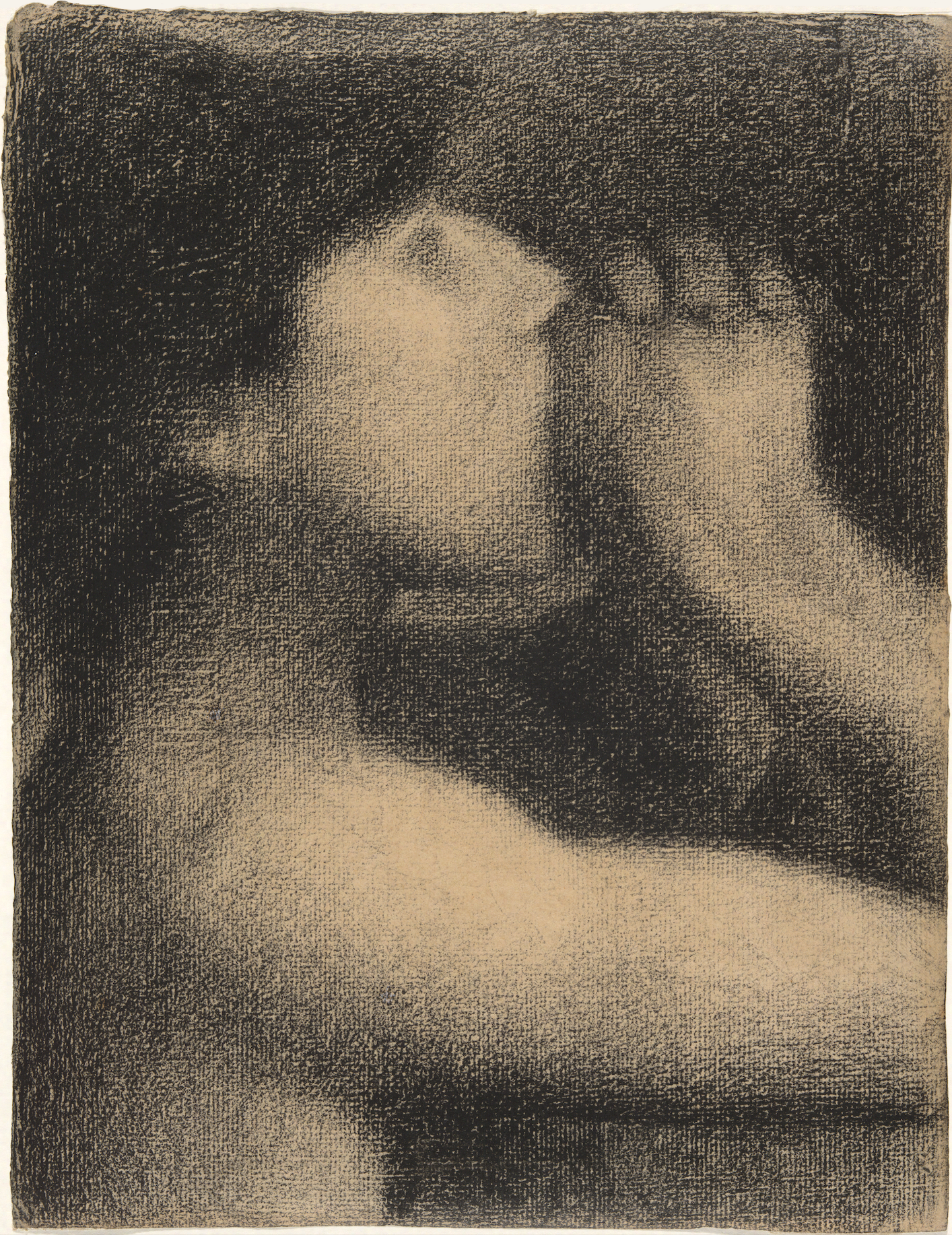

Georges Seurat,'D'écho', (Study for Une baignade, Asnières).(Bathers at Asnieres) 1859-9. Conté crayon on paper. Yale University Art Gallery. Published within M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4.

Images as visions - cloudy as to wake from a daydream, as pupils constrict into focus. Graphite grazes a surface - evoking impressions of the familiar - silhouetted forms, hazy as to be sculpted by light and air. Seurat informs his studies with information without annotation; his porous approach is gentle as to caress yet evidential as to contribute to a greater whole, made within the continuous evolution of discovery, awe-struck with a sensorial ability to communicate with the very fibre of life.

To contemplate as to be a pixel, a glitch within a system - overwhelmed with mechanised speed. A formed society, collectively concerned, faced the forest away from the factory. To tread within a world seemingly blanketed in snow, so deep as to muffle sound, and dapple an impression within the nature of a newfound page. The micro dot appears as if from the lens of the magnified specimen, of a feathered tuft, as a skin's pore, as to stare as if for the first and last time simultaneously.

Seurat’s loyal thoughts return to values treasured by workers, whose lives are monitored by others, within systems that allocate time, governed by profit. The artist’s depictions of the resting, the unposed, the staring into space - hark back to a nature poised within a pecking order - alert to position and weary of the continuum of labour. His punctum portraits of atmospheres held as a drop on the brink of falling - mediate conditions ahead of definition - they focus on time of day, tides and breath - as a clock face whose hands are removed to reimagine a life which does not tick - rather pulse.

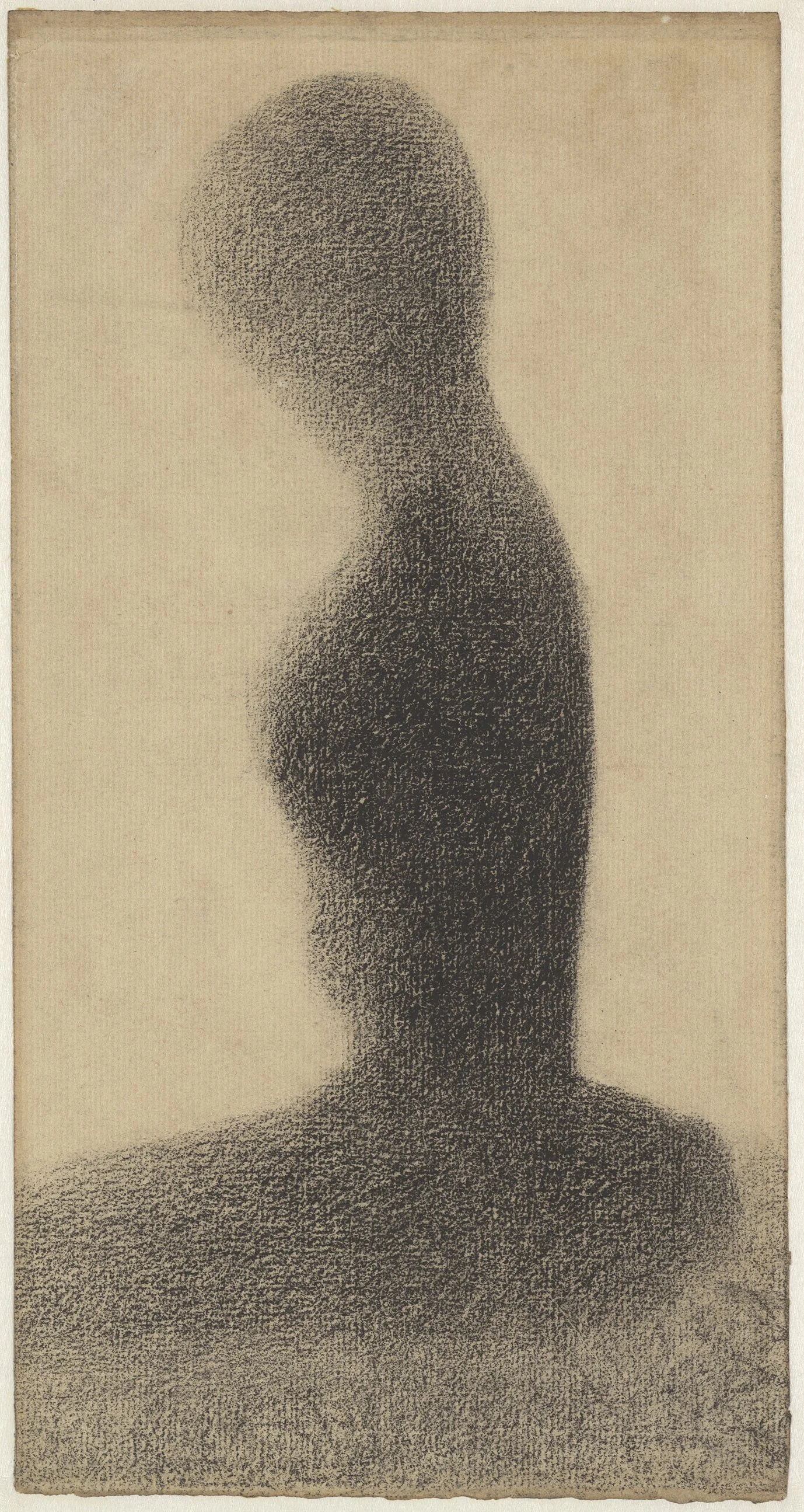

A collective technique, a shared philosophy, articulated and furthered by comrades of painters - exploring the iconography of pointillism - expressed within an undulation of responses. As a musician writes a score - a proposal of sound read in silence, so too do the Neo-Impressionists present works which await reading, translating marks made en masse to encapsulate a gesture.

Paintings further evoke a collective sense of the organic, unfathomable power of the natural world, within the overpainting of frames which appear to shimmer as reflections from a water's surface. Are we looking at an impression of nature, or are we viewing a prayer, a moment held, as a memory.

Seurat's radical sense of reduction appears amorphous as to be hewn from stone, his objects and crowds suggest a sense of searching, scanning for information, so that forms uncloud as architecture, pronounced as structures seemingly familiar yet distant from view. As to return to an ideology which prioritises the fleeting over the fixed. As to harmonise within a collective spirit of visual voices, a choir as opposed to a soloist.

And it is within this idea that denotes Seurat's influence as perpetually modern, his work is shared both with the unnamed souls he depicts and also as a member of the Neo-Impressionists to whom he belongs, collectively believing in furthering the populous than the lone.

‘Young Woman: Study for ‘A Sunday on La Grande Jatte’, 1884-5. Conté crayon on paper, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands. Acquired with support from the Rembrandt Association.

Radical Harmony, Helene Kröller-Müller's Neo-Impressionists. National Gallery, London. Until 8 February 2026.

With Thanks to Neil Evans.

A series of works by Georges Seurat are published within the 4th issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN), available while stocks last.

129. OLIVIER MILLAGOU: A SPACE BETWEEN PIN AND PARADISE.

Drawing Pin - MAC VAL - Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne.

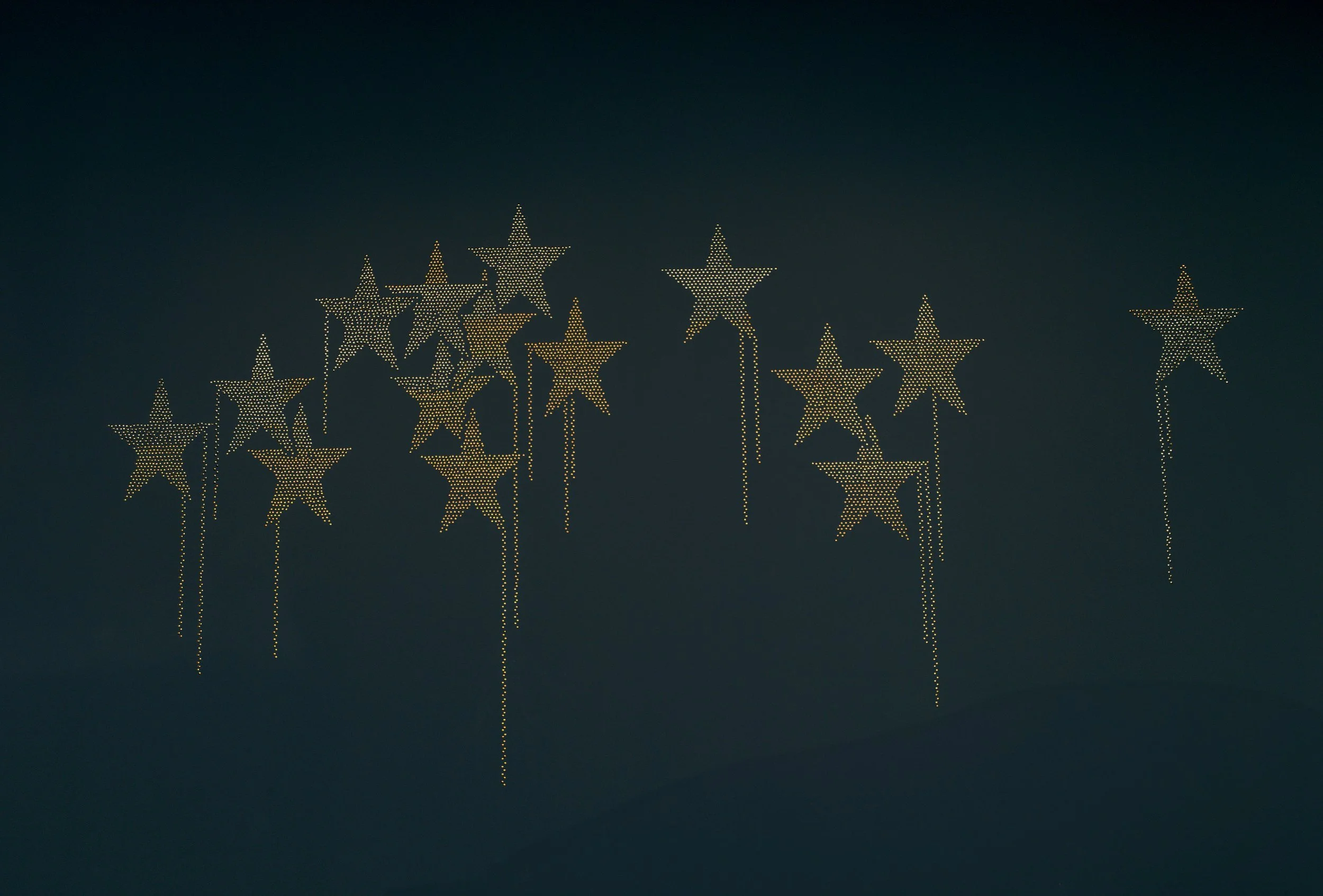

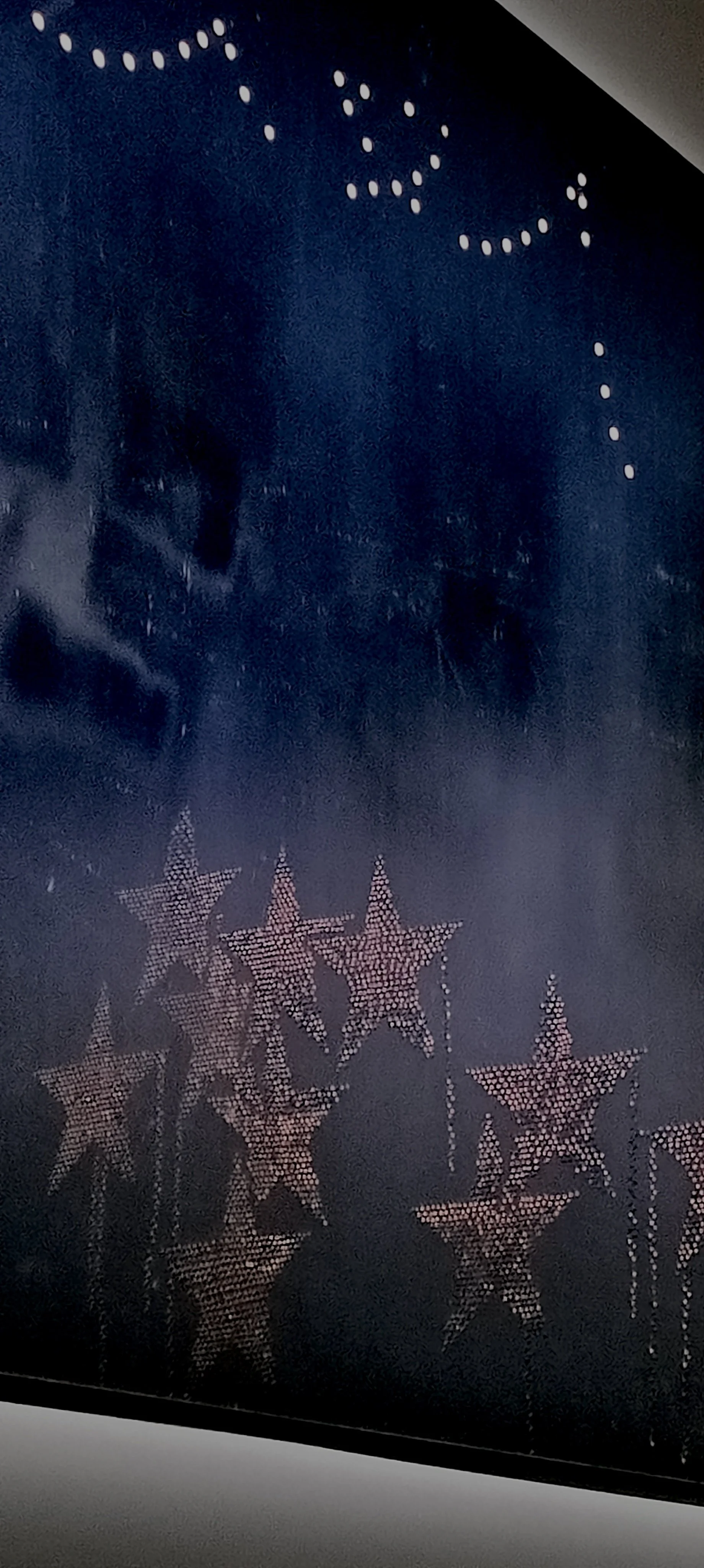

Olivier Millagou, Drawing Pin - MAC VAL - Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne.

‘I chose stars for their countless possible symbolic meanings. They can be geometric figures, celestial bodies, sporting symbols, celebrity symbols, heraldic symbols, religious symbols, as well as being found in the sea… and I also had this desire to draw a starry sky, to offer a simple representation of moments of contemplation. For a time, I tried to depict, in a way, landscapes of a lost paradise.’ O.M.

Please can you introduce the installation on show at MAC VAL?

This is a wall drawing created with gold pins on a black wall. Each drawing in this series has a generic title, Drawing-Pin. This one dates from 2024 and depicts a starry sky.

On viewing the work for the first time, the atmosphere within that space felt hallowed... the remains of something... as a frieze high on a wall, and yet also deeply celebratory - please can you discuss how you decided upon the work's installation?

This drawing is the last in the Drawing-Pins series, and it differs from my previous works because it originated from an invitation by Christoph Wiesner to participate in an exhibition at the Esther Schipper Gallery in Berlin, where all the works were to be displayed on the ceiling. I proposed the idea of a mural, placed high on a wall, with a design that varied without repeating. The method of installation is defined by the material itself: a thumbtack in a wall.

The choice of materials and application really fascinated me... and the sense of permanence and non-permanence... a site-specific installation pinned down, studded as a piece of upholstered furniture, and yet there was a sense of punk somehow, of breaking rules... and yet a feeling of such liberating beauty which felt as art nouveau...

The Drawing-Pins series began with my very first exhibitions.

These drawings arose from several desires: the first was to imagine a way to display drawings using a material I could reuse for multiple exhibitions, and produced in France (for exhibitions within the country, but also produced in other countries to avoid transporting artworks). The second was to respond to an economic and philosophical necessity of creating work without a studio. And the third, finally, was to question that moment in life when we leave behind our childhood constructs to become adults. I was interested in the idea that at some point, the posters displayed on our bedroom walls during our childhood are eventually removed. Symbolically, all that remains are the pins on the walls, becoming points that can be connected, and which can represent a remnant of what these posters may have left on us.

I started with this project by thinking about a work that could occupy a space with small things, in this case, thumbtacks, which, once the exhibition is over, become functional objects again or are reused for the next exhibition, or recycled. There was a real desire to do something with very little, and like the idea of punk, to make do with what you have on hand; in fact, the first drawings were a series of band logos.

The pin feels symbolic, somehow an invisible item which is generally used to pierce a surface in order to present another element, and yet within this work - the pin is central, and yet from a distance the entirety of the stars become something else... they become a whole, made of tiny elements...

You could find several kinds of thumbtacks commercially: some with colored plastic film, others simply made of brass. I opted for the brass version because this material can be recycled indefinitely. It represented a common, simple, and functional object.

The way I found at that time to question the consequences of the climate crisis was to systematically paint all the walls of my exhibitions matte black, thus contrasting the colours of the images I was referencing. I like this contrast, offering something humble alongside something bright, sparkling, and present, mimicking precious materials with modest ones. The idea of using materials that normally serve only as functional elements as central elements also stemmed from the desire to find ways to produce a work of art while limiting the consumption of raw materials and energy.

The motif of a star, historically, is very specific, and yet has become synonymous with magic, festive seasons and fame... a divisive symbol which sometimes evokes much pressure, and within a work made of pins... There seems to be an irresistible connection. What does the star mean for you?

I chose stars for their countless possible symbolic meanings. They can be geometric figures, celestial bodies, sporting symbols, celebrity symbols, heraldic symbols, religious symbols, as well as being found in the sea… and I also had this desire to draw a starry sky, to offer a simple representation of moments of contemplation. For a time, I tried to depict, in a way, landscapes of a lost paradise.

Olivier Millagou, Drawing Pin - MAC VAL - Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne.

128. FELIX GONZALEZ-TORRES: A SPACE BETWEEN SWEETNESS AND LIFE.

MINIMAL, Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection - PARIS.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

'Pieces presented as simple, in plain sight yet weighted with symbolism, coded for those open to appreciate the deep-seated in the seemingly superficial. For a work which sits on a surface of a gallery floor, is also deeply rooted in the subconscious of human survival and stigma.’ M-A

At first glance, what appears to be a momentary shard of light resting on a floor - a reflection from a series of paintings above deceives the eye and is in fact a mass of confectionery.

Sun bleached as an outstretched shore - powdery pale as to be made of countless shells - ground down to form a singular land mass. Still and controlled yet symbolic of a process - volatile and destructive, yet presented as a sparkling mirage.

Ivory - the colour of bleached corals which lose pigment as they die, once fluid and vital, vivid - undulating as a textile, become morbidly brittle and white.

A dry landscape of zen, reinterprets nature as eternal, maintained by shadows of the trusted - mysteriously replenishing a bodies weight - as benign strangers visit with naive intrigue, to collect a souvenir - as a piece of a soul, as to be a canable. No shoots of green spring here only contemplations grown and dissolve as the possibility of thoughts rooted in regret.

A wrapper which loses its original purpose to protect becomes an ephemeral debris - once its contents is consumed.

Pieces presented as simple, in plain sight, yet weighted with symbolism, coded for those open to appreciate the deep-seated in the seemingly superficial. For a work which sits on a surface of a gallery floor, is also deeply rooted in the subconscious of human survival and stigma.

Overwhelming in scale, as a shocking exposure - seen as a mass of countless units in plain sight - confronts a notion of confession - forcing the eye to glaze in order to witness the work as a whole, reduced to a single type - as a verbal narrative distilled to a pertinent concentration. As pointalist dots... a pox, as a virus which coagulates to form a whole - to engule and to be engulfed.

Symptoms read as provenance - tracing back to origin as forms of remembrance - yet are read as unexpected and intriguing. As the exposure of situations which are hidden from view, as shame - brushed under a carpet. Symbolised as candies readily available and yet are demonised as dangerous, yet remain to continue to tantalise as sparkling choices - pre-packaged and light - yet complex and divisive.

Torres' confectionery choice remains a forbidden state of mind, an attitude-evoking knowing metaphor. A medium belonging to memory, even whimsy, a specific campness which evokes retrospection, and it is this awkward combination which supports an overarching taught atmosphere of the unnatural. A mass of glittering, unclaimed prizes as the contents of a piñata, which remain left behind, as if an event removes the opportunity of life.

MINIMAL - Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection - Paris, until 26 January 2026.

With thanks: Jessica Seoane.

M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) contemplation and interview series will return in the spring. Thank you for reading.

127. CHANG LING: A SPACE BETWEEN MEMORY AND PROPHECY.

Don Gallery, Freize London.

If My Hometown - Plantain Garden 假如故乡-芭蕉园, CHANG Ling 常陵, 2025. Oil on canvas 布面油画, 162 × 130.8 cm.

‘Unlike the overt expressiveness often found in Western traditions, this seemingly vanishing way of seeing allows the viewer to quietly dissolve into the work through space and light to become, ever so faintly, part of the indistinct crowd.’ L.C.

Seeing your paintings during Frieze London, I was drawn to your paintings which evoked a very specific depth of energy. Directly evoking a link back to the traditions of scroll paintings… Please can you contemplate the works as a series?

‘If My Hometown’ is a body of work I began in 2024. The abstraction of hometown lies within the collective consciousness of each act of looking back. In this new era of AI, the power to compose historical memory and future prophecy is gradually slipping from our hands. ‘If My Hometown’ was born out of this sense of crisis, focusing on the dual immersion—and entanglement—of sovereign consciousness. Can a blurred consciousness still perceive the traces of life we once had?

Your application of colour is arresting, drenched and alive, the sense on seeing the series was radical as the paint still appeared to be wet - not yet fixed... Please can you expand on your reading of time within the creation of this series?

I remember being born in Hualien, Taiwan — a place near the Pacific Ocean filled with banana trees, often the first coastline struck by the warm winds of summer typhoons. No — perhaps I think I remember. Or maybe I was born in Tamsui, a small fishing town in the north. I should ask my elders, or look through childhood photographs. But what if all of that no longer exists...If this is the dual immersion (and dual disorientation) of sovereign consciousness regarding the past and future...

Half hidden within the paintings are tiny scenes which suggest human groups, immediately this tension and dialogue to the community felt important. Please can you expand upon this narrative and symbolism within your practice?

As you’ve observed, I am deeply drawn to subtle, almost elusive modes of depiction. Unlike the overt expressiveness often found in Western traditions, this seemingly vanishing way of seeing allows the viewer to quietly dissolve into the work—through space and light—to become, ever so faintly, part of the indistinct crowd.

I thought as I looked closely into your series of landscapes, how interesting the brush work is, how the paint is applied to the surface and is also pulled away, as a brush that sweeps. Please can you explore your use of implements within your practice, and do you have specific tools which you rely upon?

I have a stand for my tools — it rises like a small mountain, piled with sticky paint, cloth, dried brushes, and others soaking in linseed oil. The air is thick with all kinds of scents. Within about 1.5 meters of reach, everything becomes an intuitive tool at hand. Sometimes there’s no time to select carefully; I simply spread the paint with my hands.

The placement and selection of works presented by Don Gallery at Frieze London were very strong this year. The link to other artists was very well considered and highly sensitive, which added such a tension to the experience of viewing the works... which artists are you drawn to and what do you learn from them?

Don Gallery represents an exceptional group of artists, and I’m honored to exhibit alongside them. I’m particularly drawn to ZHANG Yunyao’s work, with its striking contrasts and cool tonalities, and I also deeply admire ZHANG Ruyi’s pieces — the layered, accumulated cacti are simply mesmerising. She will be presenting her work at this year’s Taipei Biennial.

CHANG Ling, Don Gallery, Frieze London, October 2025.

With thanks to Silvia Sun at Don Gallery.

126. LYGIA PAPE: A SPACE BETWEEN CONSTRUCTION AND CONCEPTION.

Lygia Pape - Weaving Space, Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection - PARIS.

Lygia Pape, light installation Ttéia 1,C. Pinault Collection Paris. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

As to stand between rain storms, sgraffitoed by Dürer - dissipate to nothing - flash back as a lightning bolt crashes and a silence descends. An installation of reenactment, of proposition. Rendered in the materials of man - impersonating a divine intervention. A space between construction and conception.

Witnessing Lygia Papa's installation is to imagine clouds parting as an outpouring of beams, fire down as a curtain of arrows - a torrent of targeted spines - flash to form a sacred atmosphere pierced.

As to stand between rain storms, sgraffitoed by Dürer - dissipate to nothing - flash back as a lightning bolt crashes and a silence descends. An installation of reenactment, of proposition. Rendered in the materials of man - impersonating a divine intervention. A space between construction and conception.

The taught architecture of angels - angled as a spire - pivoting to heaven and anchored to earth - as laser beams which protect and prevent - protrude an air of human - propose a prayer of belief.

Unwoven as a warp framework - the integral mesh of life. Strung as a template - as a constant. Pape's use of copper wire intrigues with complexity - immediacy and spiritual metaphor. A material of unbreakable strength - relied upon for high tolerance under pressure.

The installation of shafts of light, appear at first momentary, precious and rare, and yet as in life are in fact consistent - the sun continues to shine even when night falls. Pape's use of materials also explore this idea of acceptance - reminding us to witness the presence of now. The use of electrical wires, normally concealed, out of reach within walls, floors and ceilings, in order to conduct electricity safely are instead exposed and presented en masse. Visually minimal as giant jewellery - dazzling to witness and potentially deadly to touch - creating an extraordinary atmosphere conducted from materials traditionally considered ordinary.

There are parallels to fellow minimalist Dan Flavin, whose luminous atmospheres created with fluorescent tube lighting are reliant on literal electricity to operate. Pape's use of copper wires are disconnected from electrical charge - reliant on positioned overhead spot lights creating a controlled luminosity. Both artists imply faith within their use of light, Flavin's is internal as a sacristy lamp, Pape’s is external as reflected illumination as a ray of light or the gilt edge of a holy book.

Is the work the materials or is the work the environment that the piece sits within, or rather is tied to? Without the physical room, the work would not exist in its current form, it requires a means to keep the wire taught to enable the controlled displacement of lines to be maintained. And so, as with faith, a space is built, to officiate a practice. Is the artists also proposing a question within her series, does art truly exist outside the gallery walls?

It is interesting to also consider, just as the artist is proposing ideas of faith, positioning, authenticity and value, even after the artist's death in 2004, the work continues to be installed and seen, furthering a point of context and ownership. The lifespan of the artist is transient; the maker is eternal.

Lygia Pape, light installation Ttéia 1,C. Pinault Collection Paris. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

Lygia Pape - Weaving Space, Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection - Paris, until 26 January 2026.

125. VAL LEE: A SPACE BETWEEN MONSTER AND ME.

The Presence of Solitude The Hayward Gallery LONDON.

Val Lee, The Sorrowful Football Team (2025). Courtesy of the artist.

‘I find blind football to be a deeply evocative form of movement. Sighted players blindfold themselves and join fully blind players on the same team, relying on sound to navigate a vast field, running forward without hesitation in the dark. To me, this resonates with something that happens in everyone’s life.’ V.L.

Please can you introduce 'The Presence of Solitude'?

The exhibition can be seen as a visual constellation of performance-based scenarios. One focuses on a fictional blind football team that I formed in Aomori, where we developed movement and listening exercises over two days during a heavy snowstorm. The other centres on an immersive performance in which audiences boarded a minivan and travelled through the mountains together with three masked figures, creating a shared yet solitary experience of movement and landscape.

The sense of implication within the work is fascinating - explored through a juxtaposition of media, which created emotive and physical spaces. Please can you expand upon the sense of implication within your practice?

I think the monster figure in the exhibition is indeed difficult to fully articulate. Its presence is intensely visual, with a vivid color and imposing scale, and when it moves, it carries a palpable weight. It feels as if it is constantly gazing at you, yet you can never meet its eyes. To me, it embodies a kind of existence that requires no explanation, no justification.

The stones arranged on its shelves also resist clear interpretation; one could say they might stand in for anything. Across countless landscapes, it seems to have gathered stones that are almost devoid of meaning and brought them back to its dwelling. Indeed, stones have appeared in many of my exhibitions. This began more than a decade ago in a performance where a performer quietly took several stones out of their pocket. Later, stones appeared again in exhibitions in Mexico City, Yogyakarta, and London. Yet each time, the context, image, and meaning of the stones were entirely different.

In contrast, the blind football team plays with a ball containing bells, which becomes like another kind of stone, moving quietly through the snow. Many times, the ball can barely move in the snow at all; only the force imparted by the player can propel the ball before them into motion.

The sense of sight is particularly pronounced within the exhibition, from the featureless fringed characters, in the images, on film and represented physically. The football team in the snow, the atmosphere with the dimmed lights - all added to the feeling of watching and being watched... Please can you expand upon the focus of sight within your work?

Indeed, in my other works, there are also examples where sight becomes a central concern. For instance, in Charting the Contours of Time, presented in Kyoto, visitors enter a completely dark space and confront intense sound, keeping the body in a constant state of tension. Eventually, they look through night-vision goggles at a life-sized replica of the well-known “Human Shadow Etched in Stone” from Hiroshima, a trace believed to have formed at the moment of the atomic explosion when a person’s silhouette was burned onto the stone surface.

Similarly, in Stereoblind, which took place in the main hall of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, several performers moved among hundreds of visitors. Their actions resembled performance yet could be mistaken for odd, everyday behaviour, creating a state in which viewers could not easily determine whether the figures before them were performing or simply part of the audience.

I find blind football to be a deeply evocative form of movement. Sighted players blindfold themselves and join fully blind players on the same team, relying on sound to navigate a vast field, running forward without hesitation in the dark. To me, this resonates with something that happens in everyone’s life.

The use of a very specific colour palette within the presentation added to the feeling of saturation, both visually and emotionally. The blue of the sky and ocean and the intensity of the use of orange... Please can you contemplate your use of colour within the works presented?

From the material choices in costume design to filming, and finally to colour grading, each step involved careful discussion. It is difficult to fully explain how we think about colour, but I can say that the monster emerges from the mountains, and its presence needs to feel very strong. In that sense, part of its colour echoes the tones of the mountains, yet another part feels entirely foreign to them.

Leaving the space, I felt as though I was returning, even escaping from a trip - I felt somehow released from an experience which was both physical while also being reliant on the imagination, entranced within the music... the experience has stayed with me - disturbing and exhilarating my thoughts... Please can you expand upon your decision-making regarding the realisation of this work?

I feel that both groups of characters in the exhibition are in constant motion. Even the monster playing music seems to exist in an endless loop. To me, they form a universe charged with intense kinetic energy, yet are presented either in complete stillness or through moving images.

The decision-making process relied heavily on discussions with the Hayward Gallery team. For me, a floor plan alone is not always helpful, but the curator, Yung Ma, would suggest what would work best in terms of bodily perception — for example, choosing between projecting onto plywood or adjusting the height of the projection. The technical team, including Chris Spear, also provided measurements and advice based on the physical space and viewing angles on site. As a result, this work was largely shaped remotely first, then refined through cloud-based discussions, and only finally embedded into the physical space, element by element.

Val Lee, Valley of the Minibus (2025). Photo by Pitzu Liu, courtesy the artist.

Val Lee: The Presence of Solitude, The Hayward Gallery. Until 11 January 2026.

Thank you: Megan Edwards.

124. NINGDE WANG: A SPACE BETWEEN MATTER AND MEMORY.

Paris Photo Preview

The Deluge, detail, 15632864Z 大洪水15632864Z, WANG Ningde 王宁德, 2024. Photographic paper, modulated printing inks applied by artist 相纸、艺术家调配打印墨水堆积, 155 × 286 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Don Gallery.

‘As ‘Deluge’ observes, time is not an external flow but a process of constant generation, unfolding, and transformation. When plants leave their traces in water and light, they undergo a metamorphosis from matter to memory. In observing, waiting, and even listening to them as they dry, I too am shaped by time.’ N.W.

Seeing your work at Frieze in London, I was immediately amazed at the beauty of 'The Deluge'. Please can you introduce the work and how it came into being?

'The Deluge' draws its imagery from nature. Plants are collected, preserved as specimens, soaked, and dried until their forms are finally fixed onto photographic paper. The studio where the works are made is on an island in my hometown, located in northeastern China, near North Korea; looking at a map, it is also not far from Japan. I grew up there and am intimately familiar with the scents of these plants, their germination seasons, blooming periods, and the ways they wither. To me, they are not anonymous natural objects, but companions of my childhood. In the work, the plants are not “painted” by me; their forms are shaped collaboratively by flowing water, pigments, and time, as if they develop themselves, leaving traces on the photographic paper.

The context of a meadow is very evocative, the mix of foliage, forming a tonality, feels like a memory and yet the work is made using photography techniques, how does your relationship with your work change over time?

Plants transform from living branches and leaves into specimens, leaving behind only their shadows. This process often lasts for weeks, sometimes even longer. During this time, I am both observer and companion. The contours and textures left by the plants capture their natural progression—from fullness to dryness, from saturation to decay—and serve as evidence of their existence in the world, as well as slices of time. Moreover, the temperature, humidity, air currents, and even sounds during this period can leave traces within the work.

Sometimes, a leaf might curl suddenly with a change in humidity, or a specimen absorbing pigment will emit a faint “whispering” sound. In autumn, the studio is filled with the scent of daisies and oak leaves, and these aromas also become part of the work. In this process, I too inhabit the same span of time, quietly dissolving into the textures of the plants. My presence—my breathing, waiting, and sense of loss—is embedded alongside them. I share a fluid temporality with the plants: time is no longer merely an external, passing dimension, but a material state inscribed on the photographic paper by water, plants, and air. Each work becomes a manuscript of time, written collectively by water, light, and air.

The depth of tone within the work evokes time in a very particular way, the sense of fading away... of what remains... the implied space created within the work of removal feels particularly pronounced, please can you expand on the atmosphere created within The Deluge?

During the making of The Deluge, I often venture alone deep into the forest. Nature can be at once profoundly silent and softly murmuring, always narrating its own life stories. Plants engage in subtle and complex interactions with the air, light, and humidity. They capture sunlight and provide energy for all living things. Each plant perceives light and gravity in its own way; their forms appear still, yet they are continuously generating — a slow, almost imperceptible process of becoming that I aim to capture in my work.

The placement of plants may seem random, yet it carries an inherent order, a logic of its own. Amid my own breathing, they reveal the rhythms of life. The air, the scents, make me certain that early humans must have witnessed the same scenes; the breath of the forest, even as civilisation progresses, remains unchanged.

In nature, in the depths of the mountains and forests, breath becomes a language shared between humans and plants, allowing true communication. Plants are not merely objects to be observed; they absorb, transform, and release, filling the air with the vibrations of life. “Nature” is no longer an external object, but a continuously generating whole. Here, water, light, air, plants, and humans share the same material time; human existence depends on these living beings.

As ‘Deluge’ observes, time is not an external flow but a process of constant generation, unfolding, and transformation. When plants leave their traces in water and light, they undergo a metamorphosis from matter to memory. In observing, waiting, and even listening to them as they dry, I too am shaped by time.

As an image-based artist, I once took pride in creating natural images without relying on the element of “light” in photography. Yet deep in the forest, I witnessed the light I had previously excluded—it is hidden within the growth of the plants, within the energy they provide to humans. Only through humble listening and quiet attention can one truly communicate with nature.

I feel that the reference of nature within painting is becoming more and more focused upon in this time period, maybe this is a reaction to so many years of digital obsession. Why are you drawn to natural references?

The Deluge series began during the pandemic. During that time, we were forced to remain still, fixed within a confined space like plants. This made me look at the surrounding landscape anew, trying to understand it from the perspective of life itself.

Through evolution, plants have given up mobility, often remaining rooted in one place, silent for their entire lifespan. They perceive the world through roots, stomata, light, and humidity - not through consciousness, but through a “responsive” intelligence. In ways beyond our comprehension, they manifest the brilliance of life.

In Eastern art traditions, plants are not merely objects to be observed; they are embodiments of life itself. Nature is often personified and spiritualised, serving as an externalisation of the mind and a visual expression of cosmological philosophy. In Chinese painting, plants are frequently personified or symbolised: pine, bamboo, plum, orchid, and chrysanthemum convey not only the cycles of the seasons but also ideals of personal cultivation and virtue. In Korean painting, nature is viewed through the lens of “self-cultivation,” imbuing it with ethical meaning plants are both living beings and symbols of morality. Japanese painting apprehends nature through the concept of “emptiness,” expressing impermanence and tranquillity.

We often treat nature as mere background, yet plants remind me that they are not “there”; they share this moment with us. Their sense of time differs from ours, yet it is more profound. They do not seek meaning, but continuously generate it. When I work with them, I am not “depicting” them; I am attuning myself to a non-human rhythm.

During that period, paying attention to these overlooked or forgotten landscapes guided me to look back, to trace the depths of memory to my hometown, extending into mountains and forests. This is not romantic nostalgia, but a return to the smallest units of life, the earliest language, and the oldest temporal structures.

This can also be seen as a reflection on digital culture and “anthropocentric narratives.” In the silence of plants, I come to understand “existence” anew: not as conscious possession, but as continuous mutual manifestation with the world.

Your use of colour is very specific, the way the fluid layers pool into degradé shades is sensational, please can you expand upon your relationship with colour?

In my method, water serves both as a medium and as a recorder of time. I usually select a single tonal colour, allowing the water to seep, gather, and evaporate naturally within the structure of the plants and paper—the colour is not merely a decorative element of visual language, but a self-operating system. It diffuses according to humidity, gravity, and the direction of the paper fibers, emerging slowly like the gentle rhythm of breathing.

Merleau-Ponty suggested that colour is not a fixed property of objects, but a phenomenon revealed by the world itself through perception. Each time water carrying pigment flows across the body of a plant, it becomes an exchange of perception—I observe how the water “thinks” and how the pigment independently decides the boundaries where it will settle.

This state resonates with the concept of “wu wei”(non-action) in Eastern philosophy does not mean inaction, but allowing action to follow the natural rhythm, letting things determine themselves. When colour flows freely and diffuses, it reveals forms more complex and honest than expected; colour ceases to be merely a means of expression and becomes a manifestation of the material itself.

The Deluge 15632864Z 大洪水15632864Z, WANG Ningde 王宁德, 2024. Photographic paper, modulated printing inks applied by artist 相纸、艺术家调配打印墨水堆积,155 × 286 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Don Gallery. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) Frieze London, October 2025.

Ningde Wang, Don Gallery, Booth D32.

Paris Photo, 12-16, November 2025. Grand Palais, 3 avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008, Paris.

Thank you Silvia Sun.

123. CARTIER: A SPACE BETWEEN HOROLOGY AND HYPNAGOGIA.

CARTIER, Victoria and

Albert Museum - LONDON.

Crash wristwatch, Cartier London, 1967. Yellow and rosegold, saphire and leather straps; 4.25 × 2.5 cm. Cartier Collection. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

‘Is Crash a work of anti-jewellery? Questioning the very status and foundations of the society and clientele to whom Cartier sought to entice?’ M-A

Presented within the Victoria and Albert Museums’ exhibition of Cartier's most iconic pieces, Crash wristwatch appears more as a piece of evidence than an item of haute horology. The timepiece is radical for reasons not due to its scale or use of precious materials, its provenance or owner, but because of its startling use of conceptual thought. Possibly the most radical element of its realisation is what this tiny creation of jewellery proposes, not what it physically is.

Crash explores the immediacy of surrealism with a trick of the eye, the design utilises the Cartier iconography of fine jewellery, subverted with a technique which assumes a position of surprise, even shock; the punk notion of destruction, presented as perfect. This oxymoronic notion, which contradicts expectations, immediately throws what is considered to be normal into question, and so Cartier's bold move, created within the tiny proportions of a wristwatch, has gone on to perplex and seduce for nearly 60 years since its first release.

A sense of perversion is scintillating within the design of Crash, the timepiece must have unerved and excited the bourgeois who relied upon the storied maison to invest and adorn their lives, continuing to set an aspirational tone which suddenly involved a sense of contraction. The tension sensed within Luis Buñuel's erotic cinematic masterwork Belle de Jour, starring Catherine Deneuve, which was also presented in 1967, supported a cultural shift towards the deconstruction of social hierarchies. The film was considered outrageous because it explored taboo themes such as sexual deviancy. Depicting a wealthy woman indulging in sexual fantasies that were both sordid and surreal, challenging the hypocritical sexual double standards of the era.

Surely informed by the surrealist movements’ symbolic depictions of reality, directly linking back to the DADA concept of anti-art, the new surrealism of the nineteen sixties seems to expand this idea beyond the avant-garde of the gallery walls and into the cabinets of products and the lives of the general public. Is Crash a work of anti-jewellery? Questioning the very status and foundations of the society and clientele to whom Cartier sought to entice?

Is Crash also a collision, not between objects but a space outside of them - a rupture of time. The watchface appears to be stretched wide, breaking every rule for a timepiece previously created by the Maison - A timepiece whose face, a challenge to read, yet immediately understood as being for those who do not follow rules set by the past, rather seeing time as a fluid notion.

A typeface of empire - The designs' roman numerals appear to sink with gravity, stretching downwards as to melt like the camembert, which supposedly inspired Salvador Dali's 1931 painting 'Persistence of Memory', where a series of clockfaces melt within a landscape, a form seemingly mirrored within Cartier's wrist watch design.

Memories do persist within the storied Maison and Crash arrives at a jarring ripple on a surface historically maintained as calm control. The tenets of Cartier are recognisable and intact, the use of precious metals, the refined detailing of craft and precision all present and yet appear ruptured to unnerve with exhilarating effect - out of control, out of time, and yet perfectly aligned to its moment of creation.

It is only in London, from Cartier's trio of bases, that could produce such a symbol of change, such a talisman of revolt. Created from the workroom of a city in flux - an identity forged from the very tension between following and breaking rules. Too audacious for New York and unthinkable for Paris, Crash remains true to a London style, forever belonging to a youthful resistance to time.

CARTIER - Victoria and Albert Museum - LONDON. Until 16 November 2025.

With thanks to Tallulah Timoko.

122. RICHARD AVEDON: A SPACE BETWEEN VISIBLE AND INVISIBLE.

Richard Avedon: In the American West - Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson - PARIS.

Richard Avedon, Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

In 1979, at the height of his career, Richard Avedon, the most famous fashion image maker in the world, embarked on a series of pictures that were to become among the most influential portfolios of portraits ever recorded. His subjects were not the supermodels and cultural figureheads for whom he was best known, but of residents of the American West, far from the bright lights of New York - his subjects were the people who worked in slaughterhouses and mines, in oil fields and on ranches. Housewives, waitresses, truck drivers, farmers, cowboys, drifters and prisoners...

Two photography assistants accompanied him, as sheets of paper were stuck to outside walls as backdrops for on-the-road, open-air studios, distilling his images to elemental, indelible and evidential.

The first portrait within the 'In The American West' series was taken in March 1979, the last in October 1984, over the course of roughly 5.5 years, portraying 752 people in 189 cities and towns across 17 states. 103 portraits were selected for the final exhibition and catalogue.

Within the same period, Richard Avedon continued to make work for advertisers and Vogue magazine, including campaign imagery for fashion houses Versace and Calvin Klein. Photographing teenage star Brooke Shields in a series of controversial images where the 15 year old actor famously quips "You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing". In the same year of 1980, Avedon was to photograph, possibly the most famous portrait within 'In The American West' series, a portrait of a 12 year old girl named Sandra Bennett. The parallels between the two portraits are interesting to contrast; both images depict girlhood in different guises, with one created to sell clothing and depicting a revision of the American identity. The fitted dark indigo jeans, polished Cuban heeled boots and unbuttoned blouse worn by Shields echo the workwear of the people who mined the American West for natural resources.

The portrait of Bennett, also photographed in denim and of a similar age to the Hollywood star, possibly shows a far more complex narrative than that of Shields. Who playfully is depicted in the guise of what the Calvin Klein consumer probably imagined the American West to encompass: romance. Bennett's 12-year-old eyes are full of the reality of life where the option to imagine another identity is not afforded; her denim workwear is fit for purpose, not for fashion.

Richard Avedon, Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon, In the American West, April 30 - October 12, 2025. Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson.

121. DANIEL OBASI: A SPACE BETWEEN CONVERGENCE AND A NEW DAWN.

‘We are more than what we are today or yesterday or even tomorrow… my work communicates faith. A belief in how every one of us can do anything.’

D.O

Daniel Obasi, "Beautiful Resistence', 2020, Lagos.

To read the full interview with Daniel Obasi, collect the new issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4: Signals. Available from 18 stockists including maaspacebetween.com, The Serpentine, Jeu De Paume and Dover Street Market.

120. FELIPE ROMERO BELTRÁN: A SPACE BETWEEN SUSPENSION AND WAITING.

From the first encounter of a work by Felipe Romero Beltrán, time seems to pause. His process of dissolving into atmospheres manages to translate heartbeats of waiting for a moment which may never arrive - a time held as a witnessed prayer.

Felipe Romero Beltrán, BODIES_Grecia Evangelina. Thom’s house, 2021-2024, lambda print, 120 x 150 cm. © Felipe Romero Beltrán.

‘Migration is a thread that runs through all my work. I’m interested not only in the politics of borders but in how migration reshapes identity, language, and gesture.’ F.R.B.

Please introduce your latest body of work and publication: Bravo.

Bravo (2021–24), published by Loose Joints and presented at Fundación MAPFRE, is a photographic essay on the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande border between Mexico and the United States. The project unfolds in a landscape marked by suspension and waiting: people who arrive at this river often spend months or years in limbo, never certain if the crossing will happen. The work is structured in three movements – Closures, Bodies, Breaches – combining interiors, portraits, and landscapes. Though the river is central, it rarely appears directly; it exists as absence, limit, and political force.

The idea of re-enactment of events, of role play, of performance within your work is fascinating and something that you continue to explore...

Performance and re-enactment are central strategies in my practice. In Dialect (2020–2023), I worked with migrants coming from Morocco in Seville, I worked with the structure of theatrical acts: bodies in gestures of waiting, resistance, or play, staged on scenes they've experienced it.

Later works such as Recital (2020), the same guys read aloud from Spain’s immigration law, showing the struggle between the body and the language, and Instrucción (2022–2024), a collaboration with dancers to recreate the embodied memory of dinghy crossings, extend this performative dimension. Reenactment is not about representation but about re-inscribing bodily memory: how gestures and roles can speak to law, borders, and the politics inscribed on the body.

Felipe Romero Beltrán, Untitled, from the series Dialect, 2020-2023. Courtesy by the artist, Hatch Gallery & Klemm’s Berlin. © Felipe Romero Beltrán.

The focus of migration and the influence of it within your work and practice appears to continue to be very important to you...

Migration is a thread that runs through all my work. I’m interested not only in the politics of borders but in how migration reshapes identity, language, and gesture. In Dialect, the focus was the Strait of Gibraltar as a site of passage, with young migrants negotiating legal limbo in Spain. In Bravo, the Rio Bravo is both obstacle and horizon. These projects are less about documenting a condition than about creating a visual and performative space in which to reflect on waiting, displacement, and the transformation of the body under migration regimes.

When we first met at the Circulation(s) festival in Paris some years ago I remember your extraordinary ability to breach spaces - to join different states of consciousness within one image, the melding of a present and the sense of memory while also pushing into new territory which felt like a proposal...

That idea of “breach” resonates deeply. In Bravo, “breaches” refers both to wounds on the body and to the informal paths migrants take to approach the river. It’s a liminal state – not only geographic but also temporal and perceptual. My images aim to hold that doubleness: they are traces of what has already occurred (an empty room, a mattress) but also openings toward what could come. This is what you describe: a simultaneous sense of memory and projection. I see photography as a tool for proposing new visual and political imaginaries, for breaching the fixed categories of documentary, art, and performance.

One of the visual hallmarks of your work is gesture and grace, I remember that sense from meeting you the first time also…

Grace, for me, is not about beauty in a traditional sense, but about the dignity of these gestures, the persistence of bodies under constraint. In conditions of migration, law, and waiting, grace is a form of survival, the body’s way of holding itself in time.

Felipe Romero Beltrán, Untitled, from the series Dialect, 2020-2023. Courtesy by the artist, Hatch Gallery & Klemm’s Berlin. © Felipe Romero Beltrán.

Felipe Romero Beltrán — Dialect, MEP - 5/7 rue de Fourcy 75004 Paris. 15 Oct - 7 Dec 2025.

Felipe Romero Beltrán - BRAVO, Museum of Contemporary Art, Place de la Maison Carrée - 30000 Nîmes. 8 Oct 2025 - 29 March 2026.

Felipe Romero Beltrán - Hatch & Klemm's - Photo Paris, Grand Palais, 13-16 Nov 2025.

M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4 is available here, along with 18 international stockists, including The Serpentine, Tender, Magalleria, Jeu de Paume and Dover Street Market.

Felipe Romero Beltrán is a contributing artist to M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 2.

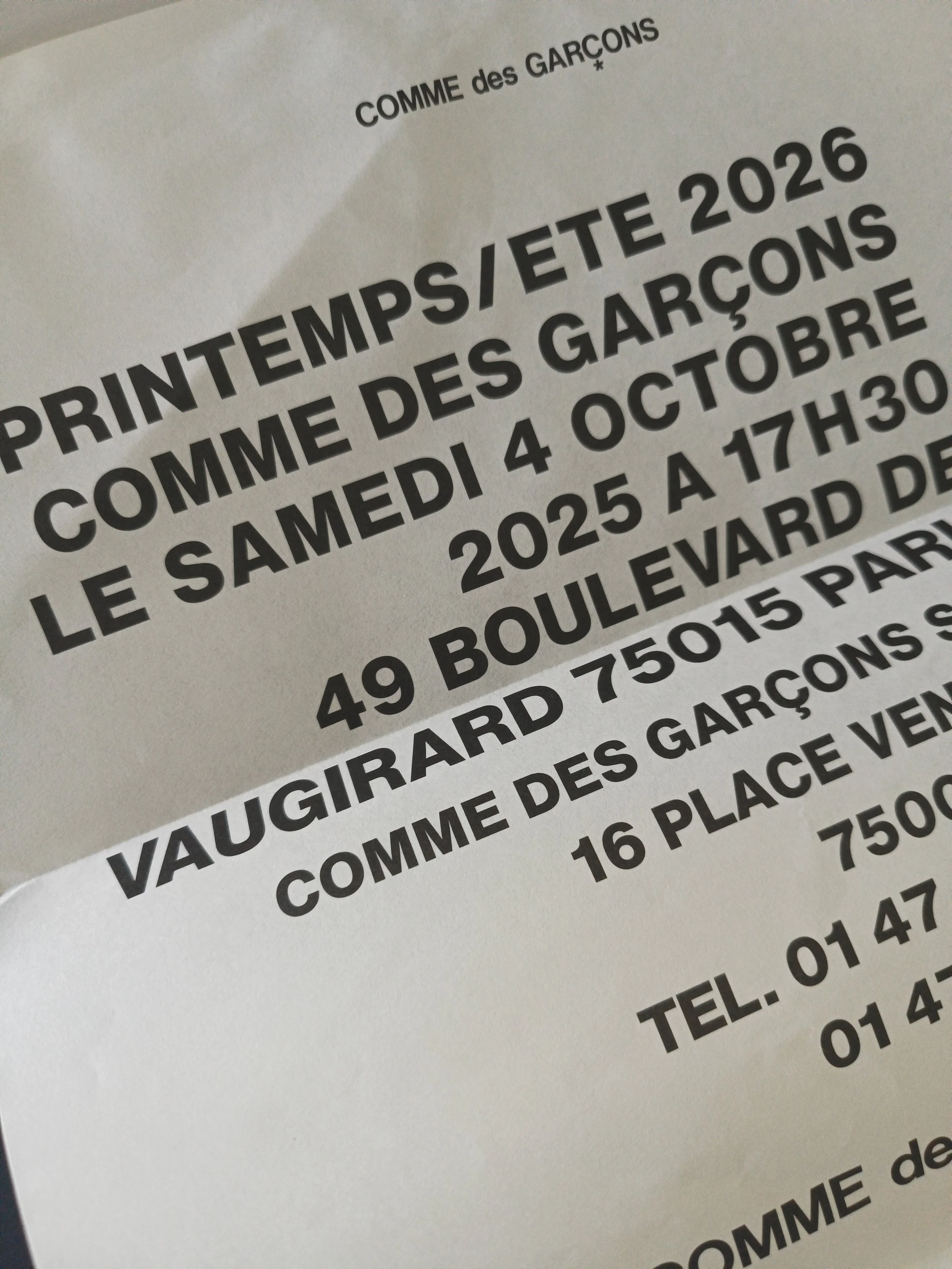

119. COMME DES GARÇONS A SPACE BETWEEN ICONOGRAPHY AND ICONOLOGY.

Printemps/Ete 2026 - PARIS.

Look 8, Comme des Garçons, pretemps/ete 2026. Image courtesy of Comme des Garçons.

Textures of dough, implied and inferred motions of kneading as well as needing, waiting, rising, knocking back - as with the stages of life, shifts in progression, and a space between moving forward and looking back. As the yeasts which enable ancient starters to continue, to ferment and produce complexities of favour due to diverse and variable natures, so too does Rei Kawakubo extract from the auras of the past to form the nutrition of next.

The notion of humble means and domestic provisions, made in preparation for sustaining life over celebration of it. In Kawakubo's hands - these quiet forms usher past - alert to temperature and temperament - spongey to the eye but fragile to touch. Sparse in decoration, the two dozen looks were delicate as Delft, unglazed and porous as a bisque firing. White washed and awaiting. Their loose, tied volumes as protective covers - coatings of contents appeared more as a metaphor for containers than decorative distractions. Threads frayed from edges ripped by hand, suggestive of rags stowed for repetitive use for domestic labour - re-presented as collages of scrim, or the horse hair inners to upholstery - normally invisible to eyes expectant of status. A state of unseen was prevalent, a space akin to a vacated storage room, fluorescent lights flatly illuminated the procession with unemotive glare, flickering off to blackness when the last model departed.

A historic language of hats, further forms an echo to a past, loaded with symbolism, possibly to C17th Holland, where a series of high-brimmed versions constructed from what appeared to be traditional fine gauge rafia and moleskin - immediately suggesting reference to the famed portraits of Dutch gentry by Rembrandt and Cornelius van der Voort. Artists whose work is now considered more a gestural depiction of the subjects than a faithful representation of reality, and so does Kawakubo, where hats arrived torn and collapsed as to suggest prior trauma, surely metaphors of now. And it is here that Kawakubo brilliantly pulls a thread from both a textile of time and the repetition of history, questioning status and the stigmas attached to the etiquette of dress and society. Both Rembrandt and Kawakubo define richly internalised bodies of work, utilising media to actively interrogate portraits of a time lived, while reducing decorative elements to intensify a personal narrative and connection. Within a collection which drew upon a state of process and distress, the Japanese creator further defined a mirror to now, the glass seemingly dusty with remnants of atmospheres, which both enchanted and disturbed.

Silhouettes, pale and ghostly, fathomed from forms which explored notions of hierarchy and privacy, continued this visual conversation of volatility, from shapes which actively appeared to inpersonate the determination and voluminous status swathes of historic nobility. At other moments, these paddings and draperies fell as to suggest disorder, disturbing surfaces to be exposed in permanence within fluctuating states. Works also inspired thoughts of storage, even choice of restoration - further connecting to fabrications which appeared as internal structures, or furniture exposed as a humble ergonomic form when removed from exterior layers of protection. And yet the 24 elements within this presentation did not feel vulnerable - exposing something which is normally unseen - raw, intensified and growing as fibres beneath ground level, as roots which draw nutrition from decomposed materials of the past in order to survive moving forward.

Thank you Thomas and Daisy.

M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4 is available here, along with 18 international stockists, including The Serpentine, Tender, Magalleria, Jeu de Paume and Dover Street Market.

118. JOY JULIUS: A SPACE BETWEEN CONTROL AND RELEASE.

A series of portraits by Joy Julius open M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4. 'Lagos Market' is interspersed with imagery by Georges Seurat and Michaël Borremans; this cross-reference highlights notions of movement and pause, identity and purpose. Through the frame of Julius, we become a part of the noise of a busy street scene, scanning for signals...

Joy Julius, Lagos Market, 2024. From a series published within issue 4 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN). Image courtesy of Joy Julius.

‘The Lagos series was a chance to observe instead of create, to respond rather than control. But I think that sense of precision and care still comes through, just through a different medium. It was about finding my language, even in a space as layered and unpredictable as the Lagos market.’ J.J.

Joy Julius, Lagos Market, 2024. From a series published within issue 4 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN). Above image unpublished. Image courtesy of Joy Julius.

Please introduce your images from the Lagos market series.

This series began pretty instinctively. I didn’t set out with a big concept; I just decided to be present and document things that I felt drawn to every day while moving through Lagos. I kept noticing patterns, colours, people, how they moved, what they wore, the Danfos (vibrant yellow and orange buses) and the brightness of the fruits in the market. Over time, I realised I wasn’t just photographing a place, but a sensitivity, memory, nostalgia. Seeing through the lens of someone returning, someone in-between places, as someone from the diaspora.

I remember first seeing some images from this series when we were installing an exhibition together of 140 designers work at The Royal College of Art last summer - and I kept seeing these little orange buses and cars in amongst all the other images... and I didn't know it was your work at first, as I knew you as the person I remember meeting in tutorials and talking about tailoring... and then I remember becoming immediately very sure that I wanted to see everything from this series...this is an extraordinary series.

Yes definitely, especially coming from someone who knew me mainly through the lens of tailoring. I think people sometimes expect you to fit neatly into one thing, designer, photographer, stylist, but for me, those practices have always been connected. The Lagos series was a chance to observe instead of create, to respond rather than control. But I think that sense of precision and care still comes through, just through a different medium. It was about finding my language, even in a space as layered and unpredictable as the Lagos market.

Your work as a designer is very precise, you are very clear with what you want and yet this series of pictures seems to engage with your ability to distil a time in another context, also in a very specific way, but also in a way where you observed others...

That’s something I’ve thought about a lot. In design, I’m building a world, constructing silhouettes and creating systems. But with this work, I had to surrender a bit. Let the serendipity of events and surroundings guide me. I was stepping in and choosing to really see, not overthink, just trusting what I was drawn to and allowing instinct to lead.

I focused on details that struck me, without needing to justify why. I still looked for balance, texture, and mood. So even though I was simply observing, I was still composing, aiming to capture an image that felt right.

Shooting in the streets of Lagos, especially in the markets, also comes with its own risks. Photography isn’t always welcomed, so a lot of the time I had to hide the camera and just hope for the best. That tension between control and release, intention and chance, is something I think really lives in the series.

I have looked at these pictures over and over again and they seem to change each time. The compositional structure is extraordinary... What do these pictures mean to you?

I’ve spent a lot of my life moving between places. I hold on to memories of growing up in Nigeria, and those memories often show up in my work. But after being away for so long, I realised I was mostly using the same references as everyone else.

So I decided I needed to go back and do my own research. To move past just memories and really connect with what Nigeria feels like to me now. These pictures are part of that. They’re my way of documenting real, recent observations and reflecting on them in ways that continue to shape my work.

What are your signals for change?

Change usually shows up when something feels off, like I’m settling for less, or when something new catches my attention. I try to notice and trust those feelings, even if I don’t get them straight away. Often, I just need some time to sort things out clearly so I can keep moving my work forward. And usually, in the end, every change and shift makes sense.

Joy Julius, Lagos Market, 2024. From a series published within issue 4 of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN). Still life image by Harry Nathan.

Joy Julius is a contributing artist to the 4th issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN), available here along with 18 international stockists including The Serpentine, Village, Tender, Magalleria, Jeu de Paume and Dover Street Market.

With thanks to Zowie Broach.

M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) will return with more interviews and contemplations in the autumn. Thank you for reading.

117. JOE BRADLEY: A SPACE BETWEEN EXHILARATION AND EXHAUSTION.

Animal Family, David Zwirner - London.

Joe Bradley, You & I, 2025, Oil on Canvas. 231.1 X 190.8cm. Image courtesy of David Zwirner.

Joe Bradley's saturated series of new paintings appear as freeze frames of avant-garde cartoons - as black outlined petri-dishes violently teeming, demanding our attention. Suites of canvases contribute to an atmosphere of parade at peak, a piñata at busting, a sugar high pre low. And yet what is Bradley's Animal Family signifying? And why are these works being presented now?

Bradley, a key member of the art world’s third generation of abstract expressionists, stands in front of 'Good World', a richly concentrated canvas which immediately evokes the heritage of the art period which he loves. A period, originally formed between the mid 1940s and 1950s. Predominantly based in New York by a collective of names, many of whom fled Nazi occupied Europe during World War two for the freedom of the United States. Creating works which were a catharsis to the horrors experienced in their home nations.

New York, the original centre of abstract expressionism, is also the home of Bradley, who’s returning focus of maps defiantly outlined in black, is first seen in 'Good World' - a patchwork of impasto blocked colour - layered to form a patina, an interplay - a cacophony - a visual slice of hysteria, with no sense of beginning nor end. We are viewing a moment which seems to be sustained throughout the twelve exhibited paintings, a technique of composition at first exhilarating and also exhausting.

Many techniques employed within the dozen canvases are actively borrowed from the roll call of artistic forefathers, he freely admits to being influenced by. Francis Picarbi’s 1940s monsters, Philip Guston 'my god - an uncomplicated love affair', Alexander Calder’s 'a big touch stone... a reaction to evil'...even using the same proportions as Willem de Kooning for a series of paintings; 'it sounded like a challenge'. The artist freely quotes from his heroes, Guston once said - 'When a painting feels hopeless, it is often the best one - as you don't have an attachment to it - to work on a painting without reservation... a painting which surpasses - has to feel unfamiliar and yet authentically its own.’

A returning sense of what appears to be cartography forms the focus of the most sustained and resolved works on show, the connection to nationality, state lines, border control and coded politics which surround these decisions seems an irresistible assumption regarding context, and yet are not mentioned within the narration offered by the artist. A scattering of stars and daisies fall as confetti over the four strongest paintings seen, tethering the collection as a whole, and offering a much-needed respite to the overt bombardment of energy witnessed.

The sense of timing and time delay is fascinating, whereas Bradley's fraternity of chosen family forefathers were known to create to the improvisation of jazz, the undulations and hypnotic rhythms which pulse through Picarbia... Calder's orchestral arches and Guston's rumbunctious percussion appear more as samples to Bradley's hip hop. Blaring colours distract from any sense of respite, proposing a question of why a state of nostalgia not lived by the artist first-hand is relevant at a time where so much needs to be addressed? It is this point that Bradley exposes, a line of modernity, a possible vulnerability, signifying a truth which, in contrast to his bombastic paintings, at times reveals possible signals, half hidden - and yet in plain sight.

Joe Bradley, David Zwirner Gallery, 11 June 2025. Image: M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN).

116. LIDEWIJ EDELKOORT: A SPACE BETWEEN CALL AND RESPONSE.

‘I came to the conclusion that maybe our instinct and intuition are not really ours, and that it is actually a universal thing… It is the collective thought process… And that we are just allowed to connect ourselves to the bigger whole.’

L.E.

To read the full interview with Lidewij Edelkoort, see the new issue of M-A (A SPACE BETWEEN) issue 4: Signals. Available from 18 stockists including maaspacebetween.com, The Serpentine, Jeu De Paume and Dover Street Market.

Join Lidewij Edelkoort in person for her Autumn / Winter 2026/7 Seminar on July 17th, 2025, Chelsea College of Arts.

115. JOEY ZHONG: A SPACE BETWEEN SEARCH AND BELONGING.

An interview with jeweller Joey Zhong - Jewellery Market Summer Exhibition - Dover Street Market - LONDON.

Joey Zhong, ‘Wrapped Topaz Ring’, sterling silver, white topaz, copper, 2024. Image originally by Joey Zhong - reprinted for a limited edition book for the Jewellery Market Summer Exhibition for Dover street Market, London, featuring 34 emergent designers, curated by Mimi Hoppen.

…My pieces tell a personal story of my family’s journey of migration from China to Australia… It is through motifs of basketry and the idea of seeds scattering that I visualise diaspora; a physical and metaphorical journey of the search for belonging. J.Z.

What is your relationship with jewellery and what does it mean for you as an object?

The very nature of jewellery is intimate, in the way it is crafted, acquired, and worn. It is arguably one of the most intimate of objects. It is layered with meaning.

Jewellery, for me, is about storytelling. As a designer and artist, jewellery is a medium through which poetic understandings of people, objects and place are translated. I see my pieces as metaphors that speak to explorations of identity and shared human experiences. I design and create wearable objects of art that aim to find resonance with people through tactility and the adornment of the body. There is a vulnerable beauty in the passing of a narrative from the artist to the viewer or wearer — a symbiosis where meaning is reinterpreted, allowing a story to form a life of its own.

You have a particular approach to using certain materials within your practice…

I have a fascination with objects made for holding and carrying. They serve as a metaphor for paths travelled. The need to hold and carry is embodied through the craft of basketry, a process that is inseparable from the hands that weave it. In my recent work, my pieces tell a personal story of my family’s journey of migration from China to Australia. I developed experimental ways of setting gemstones that reference traditional methods of weaving and wrapping. Here, gemstones and pearls play the role of seeds. It is through these motifs of basketry and the idea of seeds scattering that I visualise diaspora; a physical and metaphorical journey of the search for belonging. Dispersing from their homeland, the journey of the seed is like the migration of people: the carrying of belongings, memory and a longing for home.

My practice embodies my interpretation of jewellery as a celebration of artistry and sensibility towards materiality. The true beauty and value lie within the treatment of a material, in the ability to highlight a material’s natural beauty. I do so in the sensitive weaving of materials and gemstones. I bring together my appreciation of traditional jewellery craftsmanship with the language of contemporary design and a desire to weave jewellery convention into something new.

What have been your signalling moments of learning within your creative journey?

I think the wonderful thing about the creative journey is the endless learning. Learning through action, but also through observations of art, history, culture and interactions of the everyday.

A specific moment that opened my eyes to what jewellery could be resided in the pages of a book, stumbled across at the Central Saint Martins library. I remember finding ‘Unclasped: Contemporary British Jewellery’ (Costin, Gilhooley, 1997), during my first year in London while studying my Foundation Diploma. At the time, I was still trying to find where I could see myself situated in the creative context. As soon as I started looking through the book, I was completely mesmerised by the striking images of silver wires, seemingly pierced through the mouth and neck. It was, of course, the work of Shaun Leane for Alexander McQueen. Seeing Shaun’s work truly unlocked a path of discovery into this incredible world of jewellery, which could be macabre but beautiful, fashion yet reminiscent of traditional jewellery craftsmanship. Full of contradiction and contrast yet harmonious. It was a signalling moment that led me to pursue jewellery design. It challenged everything I thought I understood about jewellery, and it still excites me today.

I have since had the chance to express my admiration to Shaun in person, as I had the opportunity to learn from and work alongside him during an internship in 2023. It was every bit as magical and surreal as I thought it would be.

Do you have certain pieces of jewellery which you wear, and if so, can you express how they came into your life?

I can’t quite recall much jewellery being worn amongst my family growing up, or be able to pinpoint specific pieces of jewellery. It is an interesting realisation to be had. Perhaps the most meaningful pieces of jewellery to me are those that are not so often worn but can be found stored carefully at home, each with memories attached.

I have a very close relationship with my grandparents. They immigrated to Australia to care for me when I was born, and they have indelibly shaped who I am. I attribute much of my early creative curiosity to my grandma. I have fond memories of her making beaded rings, bracelets and necklaces, which she learned at our local community centre. She would make them for me to wear and even more for me to gift to my friends. There was a chunky pink lariat, rings in the shape of flowers and bracelets where strands of beads wove in and out of each other. They were made using ordinary, affordable plastic beads. I rediscovered them on my most recent visit home. I adore them not because of their material value, but because of the hands that crafted them. I have kept them for so long that the nylon threads had become brittle, so much so that some of the pieces snapped when I tried to pick them up, with beads scattering everywhere. I think there is beauty in their interaction with time.

What are your signals for change?